Sen. Elizabeth Warren made a forceful case in Tuesday night’s debate that a woman can win the White House, tackling the unpopular question that has loomed over the presidential race since Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton since 2016 – buttressing her argument by pointing to the electoral losses of the men standing alongside her on stage.

“Can a woman beat Donald Trump? Look at the men on this stage,” Warren said.

“Collectively, they have lost 10 elections. The only people on this stage who have won every single election that they’ve been in are the women: Amy and me,” she said, referring to the only other woman who qualified for the debate stage: Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar.

“So true,” Klobuchar interjected. “So true.”

In interviews over the past year, many Democratic voters have voiced anxiety about the prospect of watching Trump take on another female candidate after they witnessed the misogyny and degrading rhetoric that consumed the 2016 campaign.

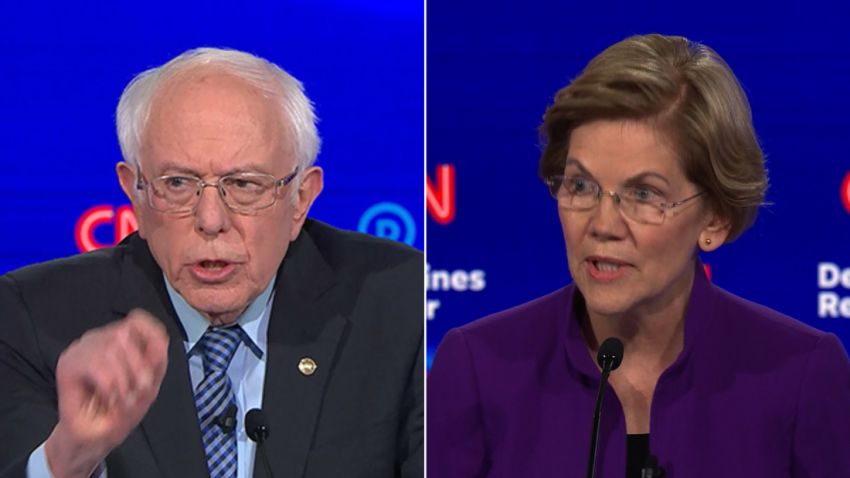

Warren had a clear opening to address that invisible barrier for female candidates Tuesday night after CNN reported this week that four sources said her longtime ally, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, told her in a private 2018 meeting that a woman couldn’t win the presidency during a discussion about the 2020 election.

RELATED: Democratic debate speaking time: By the numbers

Though Sanders has insisted he never made that comment, Warren sought to brush their differing recollections aside during the debate – “Bernie is my friend, and I am not here to try to fight with Bernie,” she said – and focused on the hesitation within the broader electorate that she must dispel in order to win the nomination.

“Here’s the thing. Since Donald Trump was elected, women candidates have out-performed men candidates in competitive races,” Warren said. “In 2018, we took back the House; we took back statehouses, because of women candidates and women voters.”

“Look, don’t deny that the question is there,” Warren continued. “Back in the 1960s, people asked, ‘Could a Catholic win?’ Back in 2008, people asked if an African American could win. Both times the Democratic Party stepped up and said, ‘Yes,’ got behind their candidate and we changed America. That’s who we are.”

Sanders emphatically denied that he made the comment in their private 2018 meeting and a chilly confrontation between the two rivals on stage after the debate – in which Warren pulled her hand back as Sanders extended his – suggested their disagreement over the content of their conversation will continue.

“I didn’t say it,” Sanders said. “Anybody knows me knows that it’s incomprehensible that I would think that a woman cannot be president of the United States. … Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by 3 million votes. How could anybody in a million years not believe that a woman could become president of the United States?”

In a later exchange, Sanders also inexplicably quibbled with Warren’s assertion that she was the only person on the stage who had beaten an incumbent Republican anytime in the past 30 years.

“Just to set the record straight, I defeated an incumbent Republican running for Congress,” Sanders said to Warren.

“When?” Warren replied.

“1990, that’s how I won – beat a Republican congressman,” Sanders said.

Warren briefly looked up as though she was doing the math from 1990 to 2020 in her head, and responded: “30 years. … I said I was the only one who’s beaten an incumbent Republican in 30 years.”

“Well, 30 years ago is 1990, as a matter of fact,” Sanders said, seeming to miss her point.

Last chance to debate before caucuses

While both the Sanders and Warren campaigns had signaled that they were looking to move past their disagreement, their exchange on gender in politics unquestionably overshadowed the sparring on other issues at the CNN/Des Moines Register debate at Drake University.

Sanders, Warren, former Vice President Joe Biden and former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg are tightly clustered at the top of the Democratic field in recent polling. In interviews, Iowa voters have expressed a profound sense of indecision – driven largely by the size of the field and what they perceive as the complexity of defeating Trump in November.

All of the candidates tried to focus on their closing arguments to voters in the last televised debate before the Iowa caucuses, while doing their best to explain how they would overcome the biggest challenges facing their campaigns.

Buttigieg insisted that he would be able to build up his scant support among black voters. Sanders argued that his unpopular embrace of socialism would not be off-putting to a broader electorate. Despite his millions of dollars of spending on television ads, businessman Tom Steyer said it would not be his wealth that was important to voters, but rather his ability to take on Trump on the issue that matters most to them: the economy.

The six candidates also engaged in vigorous ideological debates over foreign policy, trade, health care and whether free college should be extended to all Americans.

The debate started with the candidates tangling over who was best positioned to keep the country safe as they face voters who are increasingly anxious about another conflict in the Middle East after Trump ordered the targeted killing of Iranian commander Qasem Soleimani.

As expected, Sanders faulted Biden for voting in 2002 to authorize the use of force in Iraq while he was a senator for Delaware. Sanders noted that he and Biden listened to the same intelligence from former President George W. Bush and his aides claiming that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, but they voted differently on the Iraq War Resolution.

“The war in Iraq turned out to be the worst foreign policy blunder in the modern history of this country,” Sanders said. “Joe and I listened to what (former Vice President) Dick Cheney and George Bush and (Secretary of Defense Donald) Rumsfeld had to say. I thought they were lying. I didn’t believe them for a moment. I took to the floor. I did everything I could to prevent that war. Joe saw it differently.”

Biden argued that he made a mistake in voting for the Iraq War Resolution – something he acknowledged as early as 2005– but he emphasized that President Barack Obama tasked him with developing plans to withdraw the US from that conflict when he became vice president.

“I said 13 years ago it was a mistake to give the President the authority to go to war if, in fact, he couldn’t get inspectors into Iraq to stop what was thought to be the attempt to get a nuclear weapon. It was a mistake,” Biden said Tuesday night. But once Obama was elected, he said, “he turned to me and asked me to end that war.”

The Iraq War has created a bind for the former vice president because, at a time of heightened tensions with Iran, he has argued that his decades of foreign policy experience in the Senate and as vice president have made him the most prepared candidate to handle crises abroad. But his rivals, including Sanders and Buttigieg have used the vote to question Biden’s judgment.

As a veteran in the US Navy Reserve who served one tour in Afghanistan in 2014, Buttigieg has called Biden’s vote authorizing military force in Iraq “the worst foreign policy decision made by the United States in my lifetime.”

On Tuesday night, Buttigieg highlighted his military experience but did not directly attack Biden on that point, instead pivoting to a critique of Trump.

“The very President who said he was going to end endless war, who pretended to have been against the war in Iraq all along – although we know that’s not true – now has more troops going to the Middle East,” Buttigieg said.

He recalled how one of his fellow lieutenants gathered the strength to leave his one-and-a-half-year-old son, who had no idea that his father was leaving for war.

“That is happening by the thousands right now, as we see so many more troops sent into harm’s way,” Buttigieg said. “And my perspective is to ensure that that will never happen when there is an alternative as commander-in-chief.”

CNN moderator Wolf Blitzer asked Warren how she would deal with the fact that a third of her supporters say her ability to lead the military is more of a weakness than a strength, according to a new CNN/Des Moines Register poll. She noted her work on the Senate Armed Services Committee and her visits to troops around the world.

“I fight for our troops, to make sure they get their pay and the housing and medical benefits that they’ve been promised, that they don’t get cheated by giant financial institutions,” she said, noting that she has three brothers who served in the military.

Candidates clash over the ambition of their plans

The candidates engaged in a now familiar debate over the varying costs of their health care programs, particularly the “Medicare for All” plan embraced by Sanders and Warren. Klobuchar, who supports building on the Affordable Care Act, called Medicare for All a “pipe dream.”

Sanders insisted his campaign proposals would not bankrupt the country even though it would double federal spending over the next decade and insisted that his transition fund would ease the pain of likely job losses in towns like Des Moines where the insurance is central to the economy.

Warren challenged Buttigieg on his plans to make Medicare for All one among many options.

“The numbers that the mayor is offering don’t add up,” she said.

Buttigieg, in response, rejected the notion that his plan was too small.

“We have to move past Washington mentality that suggests that the bigness of plans only consists of how many trillions of dollars they put through the Treasury,” he said.

Buttigieg and Klobuchar also raised their objections to Warren’s and Sanders’ respective plans providing free college for everyone.

Klobuchar argued that the money would be better directed to job training for the professions that will face shortages in the future, like home health care, nursing assistants and electricians.

“We have to target the tax dollars where they will make the biggest difference,” Buttigieg said. “I don’t think subsidizing children of millionaires to pay zero in tuition of public college is the best use of the scarce taxpayer dollars.”

Businessman Tom Steyer was asked – as a billionaire – whether he would have supported free college for his children.

“No,” Steyer answered simply, noting that he has supported a wealth tax for more than a year. “I was one of the people who talked about a wealth tax almost a year-and-a-half ago. I believe that the income inequality in this country is unbearable, unjust, and unsupportable, and the redistribution of wealth to the richest Americans from everyone else has to end.”

This story has been updated with the events of Tuesday’s debate.