This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Anita Oberholster wouldn’t say what we were drinking. We were standing in the teaching-and-research winery at the University of California, Davis, the country’s preeminent incubator of future grape growers and vintners, and on the table in front of us were three identical wine bottles with red screw caps. Instead of a label, each bore a white strip that read sample for research, along with a cryptic string of letters and numbers.

The bottles, which came from vineyards in the Napa Valley, contained Cabernet Sauvignon from the 2020 vintage. They had all been made from grapes harvested after the Glass Fire, a blaze that tore through Napa, burning almost 68,000 acres and turning the skies orange. Nearly 30 wineries were ravaged by fire, but far more difficult to gauge was the damage wrought by smoke — which can travel, unstoppable, over a larger swath of land and seep into any vineyard’s fruit. Oberholster, an exacting South African–born chemist at UC Davis’s Department of Viticulture and Enology, is the closest thing California has to an expert on smoke and wine, and after the fire died down, wineries began sending her clusters of grapes and samples of wine in the desperate hope that she could help them prepare for the next disaster.

When trees burn, lignin, a chemical compound that gives wood much of its structure, releases into the smoke a range of volatile phenols, a class of airborne molecules. Grapes aren’t the only crop that can be affected by smoke, but their permeable skins, and the very sensitivity that allows vintners to produce expressive, complex wines, make them uniquely vulnerable. When smoke enters a vineyard, these volatile phenols get absorbed by grapes; enzymes in the grape then bind the phenols with sugars to create as many as 40 new compounds. These compounds are precursors to smoke flavors, but they’re time bombs — becoming noticeable to the palate only after fermentation and, in some cases, only after a wine has been aged.

Oberholster poured samples of the three wines, and we both picked up the leftmost glass and stuck our noses in. I didn’t smell anything smoky. “They’re a bit cold, unfortunately,” she said. Cold means less volatile, which means less aromatic. These grapes were picked from a hillside where the Glass Fire had come right up to the vineyard but the smoke hadn’t lingered. “There is smoke there,” Oberholster continued, “but you need to look for it, and you need to separate it from the fruit and everything else. If you take enough, it hits you at the back of the nose. It’s unfresh.” I spat the wine into a blue pail and took another sip. A stale, ashy flavor began to emerge. Would she consider this an extremely tainted wine? “It goes through phases,” she said. “Currently, it’s medium.”

Lifting the second glass to my nose, I thought I detected bacon. I took a sip. The flavor seemed stunted, as if it were about to reveal itself but then decided it would rather not. I sniffed again. Now the wine smelled like a spent, day-old cigarette. This wine’s grapes came from the Napa Valley floor, Oberholster said, where the smoke from the Glass Fire had lingered for days. It had the most exposure of the three Cabernets, she added.

The third Cabernet smelled better than the others. When the wine first touched my tongue, it tasted like something in the vicinity of berry juice. “Because there’s a lot there to mask,” Oberholster said, meaning the wine’s other qualities — its fruit and tannins and acid — were strong enough to compete with any smoke compounds, at least initially. Sure enough, the longer the wine was in my mouth, the more sooty and dead it tasted and the more I wanted to spit it out.

Major wildfires first seriously threatened a California wine region — Mendocino County — in 2008, but not until 2017 did they pose a significant danger to the state’s most hallowed vines. That October, a string of fires — including the Tubbs Fire, the most destructive in state history up to that point — burned more than 110,700 acres in Napa and Sonoma counties. Ash and smoke hung in the air for days. Alisa Jacobson, a winemaker who would later help form the West Coast Smoke Exposure Task Force, told me Napa had initially resisted talking about what that smoke might mean for California wine. The industry depends on marketing, and it’s easy to understand why a high-end winemaker would be loath to blemish its carefully nurtured luxury brand with a term that is dreaded and almost taboo in the valley: smoke taint. “That was a huge problem,” Jacobson said. “People wanted to say, ‘Oh, smoke taint doesn’t exist.’ They didn’t want the media or anyone to think they were going to get smoke in their wines.”

The 2020 fires were a turning point for Napa’s grape growers and winemakers. The first of them hit earlier in the season than the 2017 fires had, and many grapes were vulnerable because they hadn’t yet been harvested. And when the Glass Fire arrived in late September, it devastated the later-ripening varieties still on the vine — in particular, Cabernet Sauvignon, the grape with which Napa is almost synonymous and the basis for California’s preeminent luxury export.

As we got ready to leave the tasting room, Oberholster gave me one of the bottles of Cabernet Sauvignon to take back to my hotel so I could try the wine after it warmed up. “Pour yourself a glass,” she said, “and see if you can get through it before it starts getting extremely off-putting.”

When California pioneers set out to make wine in the 19th century, it was inevitable that they would plant Cabernet Sauvignon, one of the world’s benchmark red-wine grapes and the foundation of most of Bordeaux’s famous reds. But the kinship between California and the Cabernet Sauvignon grape wasn’t codified until the 1940s. Most of the state’s vineyards had lain dormant during Prohibition, and after its repeal, two audacious scientists at UC Davis — a viticulturist named A. J. Winkler and a plant physiologist named Maynard Amerine — sought to resurrect the industry. They divided California into five regions based on their “growing-degree days”: the average number of days in each season when the temperature exceeded 50 degrees Fahrenheit, which they deemed the threshold for California grapevines to grow. By pairing each of these regions with their analogues in Europe — where, over the centuries, winemakers had figured out which climates were best suited to which grapes — Winkler and Amerine could give growers guidelines for what to plant where. Napa was deemed primarily regions II and III with Cabernet Sauvignon its varietal soul mate. The Winkler Index, as it was known, became gospel among California grape growers.

In 1976, when the Cabernet-anchored wines of Bordeaux were still the reds to beat, a British wine merchant gathered critics in Paris for a blind taste test of some of the best French and California wines. The 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, made in Napa, placed first in the red category, besting French premiers crus including Mouton Rothschild and Haut-Brion. The tasting, which came to be known as “the Judgment of Paris,” caused a furor in France and put Napa on the world’s fine-wine map. Warren Winiarski, Stag’s Leap’s proprietor, called it “a Copernican moment.”

It wasn’t just Napa that gained recognition. The label of the victorious bottle, above the name of the region and estate, also bore the words CABERNET SAUVIGNON. This was unusual: At the time, many people who drank Bordeaux or Champagne might have had no idea which grapes went into making it. But in California, ambitious winemakers, likely wanting to set themselves apart from the jug-wine empires of Almaden and Gallo that shamelessly named their screw-cap plonk after famous European wine regions (Burgundy, Chablis), were increasingly labeling their wines by grape variety. Which meant you weren’t just drinking a Napa red; you were drinking a Napa Cabernet Sauvignon.

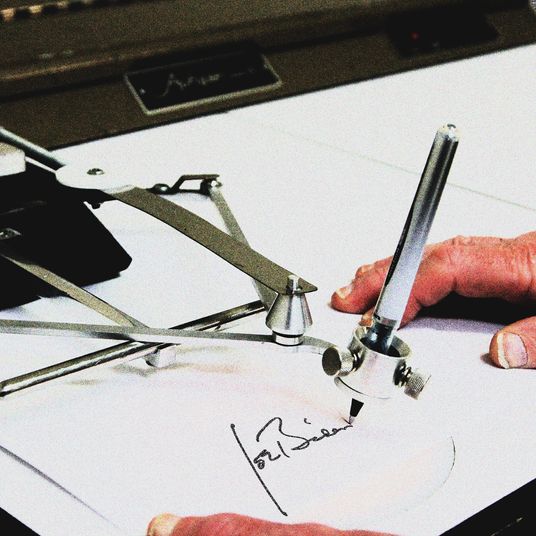

But if there was one person responsible for launching the Napa Cab into the world, it was Robert Parker, who, in 1978, founded a Consumer Reports–style wine review called The Wine Advocate. In a field rife with mystical talk of terroir and hidebound deference to traditional hierarchies, Parker introduced a 100-point scoring system that appealed to the average American consumer. By the late 1980s, he had become the most influential wine critic in the country, his scores driving which bottles retailers stocked, which vintages appeared on restaurants’ lists, and which ones customers asked for — even which flavor profiles got produced. (He insured his nose and palate for $1 million.) As of 1989, of the nearly 100,000 wines Parker had tasted since launching The Wine Advocate, he had awarded less than two dozen perfect scores and almost exclusively to French wines (with a California wine making a rare appearance in 1985). But he began to warm to Napa Cabs, bestowing a 100 on a 1991 vintage, then on a 1994. With the 1997 vintage, Parker gave 100’s to five Napa wineries at once — including one to Screaming Eagle, which was available for $125 a bottle, then considered radically expensive for an American wine. Parker praised the 1997’s “extraordinary purity, symmetry, and a finish that lasts for nearly a minute,” and a phenomenon was born. The Napa cult Cabernets, as the new wave of wines came to be called, were often produced in tiny batches, available only through impossible-to-get-on mailing lists, and came with a luxury price tag (today a bottle of Screaming Eagle costs $1,250).

Meanwhile, Napa had been dealing with an infestation of phylloxera, a pest that feeds off the roots of grapevines. Many growers needed to replant their vineyards, and they were beginning to see the fat profits they could make from Cabernet. With Napa land prices beginning to soar, they needed those profits to justify their mortgages, further cementing the bond between Napa and Cabernet. In 1997, Parker reviewed 133 Napa Cabs; in 2007, he reviewed 460. The Cab-copycat wave became unstoppable. By 2020, 51 percent of Napa’s vines were Cabernet, double the amount in 2007. Today, nearly all of Napa’s most prestigious wines are made from the grape, and while Napa bottlings represent only 4 percent of California’s wine grapes, they make up 30 percent of the value of the state’s wine. The California Cab would gain global renown for a consistent richness — a reliably intense, high-alcohol, lip-smacking fruitiness — missing from its French inspiration.

Producing it requires exacting conditions to be in place. To properly ripen into the jammy powerhouses that have been in vogue the past few decades, the Cabernet Sauvignon grape needs to hang on the vine into late October, which is peak fire season in California. It is a thick-skinned grape, vinified by leaving the skins, where most smoke compounds lodge, in extended contact with the juice. The same fruit on which untold fortunes and labor have been spent to create many of the world’s great wines and most of California’s, in other words, is now staring down a threat almost cosmically tailored to wreak its destruction.

Deer Park was just leveled,” Alan Viader recalled. It was a morning in mid-February, and we were on the crest of the hill overlooking the main vineyard at Viader Winery, a 4,000-case direct-to-consumer producer founded by Viader’s mother, Delia, in Napa in the late 1980s.

Viader was talking about the Glass Fire, which had started before dawn on September 27, 2020. The fire originated near the winery and quickly made its way around the reservoir at its foot, then started burning up the hill, accelerated by dry grass on the vineyard floor and pushed along by the wind. Viader was at his home 15 miles south of the winery, and when he was finally able to get to the property the following night, fallen trees on the ground were still burning. Aboveground, a storage building had been incinerated, as had an irrigation building full of pumps, tanks, and pipes. The Glass Fire was not fully extinguished for 23 days. Afterward, Viader and his crew went vine by vine, cutting into each one to check its health and make sure the sap was flowing. Most of the Cabernet Franc vines survived because they were further from the flames, but the vines of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes, which anchor the Viaders’ wine, were decimated.

Considering that it was the worst wildfire ever to strike Napa and that his winery had been at the center of it, Viader had been, in many respects, lucky. A little over a month earlier, another blaze — the LNU Lightning Complex Fire — had begun to burn ten miles away from his vineyard, and Viader, anxious about the possibility of more flames, rushed to harvest the crop, pulling all-nighters to pick the grapes as soon as they were ripe. By the time the Glass Fire arrived, the bulk of his grapes was already fermenting in concrete tanks underground, unharmed. The Viaders had always kept their trees pruned and limbed and clear of buildings, and the barn survived, as did the all-concrete winery and stone tasting building. But one and a half years later, as we walked the property, there were still signs of damage: ember holes in a metal sign in front of the tasting room, trees standing but stripped of bark. In the vineyard, rows of trellis wires slashed down toward the reservoir. Here and there, a T-shaped vine hugged a trellis, but most were empty. At the end of some of the rows were bundles of dried vines that had recently been pruned, but they were nowhere near the volume that would be heaped there in a normal year.

Viader is still going back and forth with his insurance company over how much of his losses it will cover. Until 2020, vineyards themselves, being lush and irrigated and manicured, were considered firebreaks not requiring extensive coverage. Like a lot of other winemakers in his situation, Viader didn’t get his policy renewed. The best he can hope for is a much smaller umbrella courtesy of the state’s FAIR Plan program, which he says won’t insure more than $3 million.

After the Glass Fire, Viader began preparing for the next time. We passed a pile of what looked like industrial-strength Super Soakers: They were “water axes,” gas-powered, high-pressure pumps with fire-hose nozzles that can shoot a blast of flame-dousing water a hundred feet. At the winery’s front gate, he had posted a reflective sign listing the main features of the property (one residence, one winery, x number of tanks, the locations where fire engines could turn around) and other information for firefighters. In January, Viader enrolled in the local firefighting academy to become a volunteer, and today he wore a fire-dispatch scanner on his belt. The road we were walking on was going to be widened, he told me, to give fire trucks easier access. “Now that I’m driving one,” Viader said, “I know exactly what they need.”

However diligent Viader’s preparations for flames, there’s much less he can do to guard against smoke, which can come from anywhere, including the properties of less fire-savvy winemakers. Back in 2017, the Tubbs Fire steered clear of his vineyards, but two blocks of his Cabernet Sauvignon were still hit by smoke. Viader experimented with a few methods to mitigate the impact or mask it — trying various yeasts, fermentation temperatures, and oaks and adding tannins — and still ended up selling the wine in the bulk market that year.

When fires swept through Northern California in 2020, casting shifting palls of smoke for more than two months, other winemakers were forced to make agonizing decisions about whether to even bother producing their wines. Napa has the most expensive farmland in the U.S., and the surest way to profit is to make pricey bottles of Cabernet; once you’re selling a luxury product, though, even minor imperfections can be fatal. “Maybe at $20 you’re okay with a little smoke impact,” said Jacobson, who, at the time, was a winemaker at Joel Gott Wines, “but at the $200 price point, you’re not okay with any.” One consulting winemaker estimated to Wine Spectator that only 20 percent of the Napa 2020 crop would be bottled. Some wineries didn’t make any wine at all, while others made only a fraction of their usual output or sold it to mass producers instead of under their own labels. Some wineries improvised — Hangar 1 made a vodka called Smoke Point from tainted Napa grapes, and Boich Family Cellar turned its grapes into brandy — but California’s wine industry, by one estimate, suffered $3.7 billion in losses in 2020. Many vineyards and wineries that are the source of California’s fabled Cabs became uninsurable.

In the time-shifted reality of winemaking, for the next few years Viader has wine to sell. The 2018s are only just now being released. The 2019s are in the cellar, bottled and being labeled. Soon, the 2020 vintage will be bottled too. During the LNU Lightning Complex Fire that August, the high winds pushed most of the smoke away from Viader, but on the fourth day, his grapes were briefly exposed to it. “To be sure and extra careful,” Viader said, he sprayed the grapes coming out of the vineyard with ozone water. He also shortened the time the juice had contact with the skins and fermented the wine at lower temperatures, another technique for reducing extraction of smoke compounds from the skin into the juice. The wines, he said, came out great, but the 2020 vintage may be the last normal one for a while; it will take around four years for the replanted vines to grow back.

California wine is a $40 billion-plus industry, but only in the past few years has anybody paid much attention to the threat of smoke. Until 2017, much of Oberholster’s research at UC Davis skewed rather arcane (see, for instance, her paper on “tracing flavonoid degradation in grapes by MS filtering with stable isotopes”). Then came the Tubbs Fire and, on its heels, three additional blazes that swept over Napa. Winemakers sued their insurance companies claiming millions of dollars of wine had been lost to smoke taint. UC Davis’s Oakville vineyard, which helps fund the experimental station where some of Oberholster’s grape research takes place, was damaged by smoke too. Oberholster saw how little work had been done on the problem, how everyone in the industry seemed to be flying blind. To the extent that smoke taint had received scholarly scrutiny, the papers all came from the University of Adelaide in Australia, where Oberholster, the daughter of a wheat and canola farmer, happened to have obtained her graduate degree. Australia had been dealing with smoke taint since 2003, but there was a lot the Australians didn’t know, and not everything they did know applied to California.

From her colleagues in Australia, Oberholster learned that it isn’t enough to test grapes for the volatile compounds detectable right away; one also has to test for the compounds that reveal themselves only months later, when fermentation unbinds the phenol-sugar compounds and releases the volatile phenols and their smoky flavors. She had to inform devastated grape growers that there are no easy or one-size-fits-all fixes. Unless growers know exactly where the smoke in their vineyards came from, how long it was there, and exactly when it was created, its impact on their grapes will be unpredictable: One could have a vineyard next to a fire, but grapes 20 miles away could be more affected because of wind direction or topography. The best thing a grower could do, Oberholster said, was something that had been tried in Australia: Ferment a small batch of wine in a bucket and have a panel of tasters assess it — ideally five or more, as a certain percentage of tasters either don’t taste smoke taint or are overly sensitive to it. People used to alchemizing $1,500 Cabs in state-of-the-art steel vats, in other words, might have to resort to making wine in a plastic pail.

Of all the manipulations to which a California winemaker might deliberately subject his juice, one of the most common is toasting oak barrels with the express aim of imparting a smoky flavor to the wine inside. But a “coffee or caramel roasted-nut quality,” as Viader put it, is a long way from smoke taint, which he compares to “drinking out of a used ashtray.” Winemakers had to make a difficult trade-off: Pressing grapes and leaving the juice in contact with the skins is how they extract the most flavor, but it’s the surest way to maximize the number of smoke compounds present. Some winemakers took the path of minimizing skin contact — making white wine, which requires no skin contact, or rosé, which requires minimal. But whites and rosés, for the most part, don’t fetch nearly as high a price as reds, and minimizing extraction means getting a lot less juice out of the grapes, which further cuts into profits.

Oberholster is working to address the smoke problem at every stage of the winemaking process — beginning with the grapes on the vine. Last year, she and her students used the campus vineyard to conduct a “barrier” test, trying out different compounds that could potentially insulate fruit from smoke. First, they built a hoop house from PVC tubing, construction plastic, and duct tape. Then they sprayed bunches of grapes inside with a dozen types of barriers — from a clay solution to activated charcoal — and smoked them. UC Davis owns vineyards in more prestigious locations, including 40 acres in Napa’s Oakville district, but, Oberholster said, “I think they” — such neighbors as the blue-chip label Silver Oak — “may be slightly upset if I bring a smoking tunnel in there.” She was in the midst of analyzing the results, yet even if one barrier worked, other issues remained: When does one spray? If one’s vineyard is in the path of a fire, will there be time to treat the grapes? How does one get the barrier compound off the grape before crushing it?

Oberholster is also trying to get better at predicting, after the smoke has cleared, which vineyards are likely to have been harmed and how badly. She and her colleagues are working with a private company to install a network of atmospheric sensors in vineyards all over California, Oregon, and Washington that will provide data on exactly how smoke breaks down as it moves. And she is looking for ways to treat wines that have already been finished. If the smoke impact is low, she said, some filtering techniques, such as activated charcoal or reverse osmosis, can largely remove unwanted smoke flavors. But if the wine is more affected, using a more powerful filter will, in the process of removing smoke compounds, strip the wine of its body — and the ineffable qualities that, if detected by the Robert Parkers of the world, could be worth millions. To avoid this, she’s working with other chemists who are trying to develop smart bombs: resins that, like prescription drugs, can target precise compounds and leave the others undisturbed.

As much as winemakers have brought science to bear on their craft, it remains maddeningly at the mercy of artistic touch and spontaneous acts of God, and the threats of smoke and fire have only expanded the uncertainty. A winemaker, fearing smoke taint, might send grape samples to a lab and receive volatile-phenol numbers that suggest there’s no problem, so the grower’s insurer won’t settle a claim. But six months later, after fermentation, the wine made from those grapes may not taste right, so a winery won’t buy them. Oberholster is trying to create a more accurate scale for winemakers when assessing the lab numbers and to establish benchmarks for acceptable and unacceptable levels of smoke compounds. With this knowledge, a paralyzed grape grower may be able to make better decisions on whether to pick, when to pick, or how to write into a grape-purchase contract the specifics of what will and won’t be tolerated in the way of smoke impact.

As if smoke and fire weren’t bad enough, the prized Napa Cab, as we know it, is facing an even greater existential threat. As temperature extremes have become more common in recent years, the world’s wine maps have begun to shift. Places never before mentioned in the same breath as “wine country” are bottling vintages worthy of your local retailer: We now have Chinese Cab blends, Norwegian Rieslings, and critic-pleasing English sparkling wines. And regions where quality has historically fluctuated with vintage — depending on that year’s weather — have been consistently producing good wine year after year. Gone are the decades when a top winemaker, loath to dull its luster, might sell wine under its own name only four years out of ten. “Some of that’s better winemaking equipment and techniques,” Massican Wines’ Dan Petroski said. “But a big part of it is weather.”

Even the stodgiest regions have begun to prepare for a warmer future. Bordeaux — likely birthplace of the Cabernet Sauvignon grape, home to some of Europe’s most storied reds, and historically not synonymous with bleeding-edge innovation — has been experimenting with nontraditional grape varieties, starting with a broad field of more than 52. Last year, the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité, starch-collared national guardian of all that is comme il faut in French wine, officially sanctioned the region to plant six “new varieties of interest for adapting to climate change,” including such obscurities as Arinarnoa, Castets, and Liliorila.

After the 2017 fire in Napa raised questions about whether climate change was to blame, Petroski, who had been the winemaker at Larkmead Vineyards since 2012, winning accolades including the San Francisco Chronicle’s Winemaker of the Year, took it upon himself to go into the winery’s records and track the dates of the growing season for the previous ten years. Without anyone noticing, it seemed, the season had shifted one month forward over that period, the vines hitting peak ripeness earlier and earlier each year. Petroski saw several causes. Since a big replanting in 2007, Larkmead had been growing healthier vines. And with the hegemonic power of Robert Parker having retired along with the critic, and Petroski’s own tastes evolving, he had been shifting the style of the wines away from the high-alcohol fruit bombs favored by Parker toward lighter wines more reflective of their terroir, which meant not leaving the grapes on the vines so long. But climate was undeniably a factor too, and that’s when Petroski began to believe Cabernet Sauvignon’s days in Napa might be numbered.

Maybe because he was born in Brooklyn and moved to Napa only in 2007, Petroski isn’t hung up on an immortal marriage of county and grape. “It’s a 25-year-old industry, in my opinion,” Petroski told me over coffee in New York last fall. “That’s why I’m like, Why are we so stuck on Cabernet? You can look at all the plantings in all of Napa Valley from the ’80s and Cabernet was not even in the top five.” In the ’70s and ’80s, Napa was more focused on white wine for reasons, in Petroski’s telling, of lifestyle. “You can’t snort coke and drink red wine,” he said, “ ’cause you’re just fucking up your whole retronasal.” Petroski, whose background is in marketing and who has a knack for packaging catchy narratives, recalled thinking, “We’re going to tell the king he’s no longer king. Cabernet’s gone. And the math and the science and the trending is saying that. Cabernet is done.”

At the time, Larkmead’s grapes were 75 percent Cab. With the owner’s blessing, Petroski decided to plant research vines on the property using great wines from warmer climates as his guide. “If someone comes in here and says, ‘Why are you planting Tempranillo?’ I’d say, ‘Sorry, bro, don’t you know about Vega Sicilia? It’s $800 a bottle, and it’s Tempranillo and Cabernet.’ And if they ask, ‘Why are you planting Touriga Nacional?’ I’d say, ‘You’re not familiar with Barca Velha? It’s only been made 19 times in the past 100 years, and it’s $500 a bottle. It’s one of the greatest wines in the world.’ I’ll say, ‘Hey, I’m looking at warmer climates. What regions are making great wines in warmer places? What wineries are models for us?’ ” In Petroski’s view, Cabernet may have another 20 years in Napa before it starts to have a real problem. He’s not waiting to come up with a solution: He left Larkmead last year to focus on his white-wine-only Massican brand, which he runs from his iPhone, sourcing the grapes from other people’s vineyards and turning them into wine in someone else’s cellar.

When he started talking about Cabernet losing its throne, Petroski said, “my nickname became Doomsday Dan.” Today, lots of Napa wineries are undertaking similar experiments. Viader told me that, after the Glass Fire, he started shifting his wines away from the Parker-favored powerhouse style and back toward the fresher, more acidic, lower-alcohol style his mother had made when she was first starting out; these wines can be made from grapes picked earlier, shortening their exposure to fire risk. And though he was less pessimistic about the future of Cabernet, Viader was setting aside 10 percent of the vineyard to experiment with varieties like Malbec, Grenache, Tempranillo, and Touriga Nacional — “all hardy varieties from arid areas of the world,” he said. “Kind of thinking ahead for the climate.” “It’s recognized now as an existential threat,” Petroski said. His peers, he has noticed, are “weaning themselves off Cab or looking at What are the future options?”

Petroski’s prophecies may soon get a scholarly imprimatur. Between 1895 and 2018, the average temperature in California increased 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit. In 2012, wine climatologist Greg Jones pointed out that if current trends continue, by 2050 Napa would be “a table-grape region.” While Cabernet is primarily a region II and III grape, according to the Winkler Index, Napa’s increasing annual growing-degree days threaten to push more parts of the valley into the region IV category, suitable for warmer-climate grapes like Sangiovese.

A few years ago, Winiarski, whose Stag’s Leap Cab turned the wine world upside down at the 1976 Paris tasting and who had long considered the Winkler Index his “bible,” approached UC Davis with a proposal. Now 93, he had seen the skies over Napa darken during the 2017 fires and lost several structures at his Arcadia Vineyards to the flames. He began to think the index was due for a revision — to catch up to advancements in the world of plant science as well as to the changing climate. It was at UC Davis that, three-quarters of a century earlier, Winkler and Amerine had done their pioneering work on the relationship between California weather and grapes, so Winiarski gave UC Davis $700,000 to overhaul it.

The job fell to Beth Forrestel, a professor of viticulture and enology who had worked in restaurants in the Bay Area before going to graduate school for ecology and evolutionary biology. She had been studying the impact of “extreme heat events” on grapes and the wines made from them; since starting to reassess the Winkler Index, she has begun cultivating 50 grape varieties in three vineyards. Much of her research has focused on debunking conventional wisdom. Although Bordeaux and Napa are often compared, Forrestel was well aware that they have significant differences. For one thing, Bordeaux gets rain in the summer, while Napa does not. Napa has more varied soil types and microclimates and actually spans four or five Winkler regions. Part of what Forrestel is trying to do is come up with a much more detailed, granular map. Instead of growing-degree days, she’s looking at the more precise growing-degree hours, temperature minimums and maximums, soil depth, rootstock selection, and radiation, elevation, and irrigation. She thinks that it will still be possible to make good Cabernet in Napa but that the region will need to diversify both vines and growing practices. There will be more grapes and more sub-regions. The style of Cabernet may have to change. And Cabernet may be grown in places it hasn’t been grown in the past, such as Carneros, a cooler area that includes pieces of both Napa and Sonoma and has traditionally focused on Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. The default will no longer be “Napa Cab.”

Forrestel, who hopes to start publishing her findings in the next couple of years, understands Napa winemakers’ anxiety: “We’ve constrained ourselves economically and become tied to Cabernet in many ways. I think that the fear, too, is when you plant something else, can you sell it?” At the same time, she has been heartened to find “a lot of buy-in to this Winker Index project. It’s mind-blowing because I anticipated that growers wouldn’t be interested in sharing much information, but people want to figure out what to do.”

Not all of them are betting on Napa. Last year, after nearly two decades working there, Jacobson, the former Gott winemaker, moved 360 miles south and bought two vineyards in the Santa Ynez Valley. “Santa Barbara has been relatively smoke free the last ten years,” she said. “That wasn’t an accident.” There’s more water in the ground in Santa Barbara, so even without rain, the vines have more to drink; land is cheaper, and Santa Ynez doesn’t have as many big forests, which, if they catch fire, create the blankets of dense smoke that spell doom for nearby grapes.

In 2020, when Jacobson still worked at Gott, she had to evacuate her home during one of the fires. “There’s been an evacuation every year since 2017,” she told me. “We keep saying, ‘It’s a wild year,’ but now we say that every year. It’s getting pretty old.”