In many developed countries, the rate of twin births has doubled or more than doubled over the past few decades, according to a recent study published in Population and Development Review.

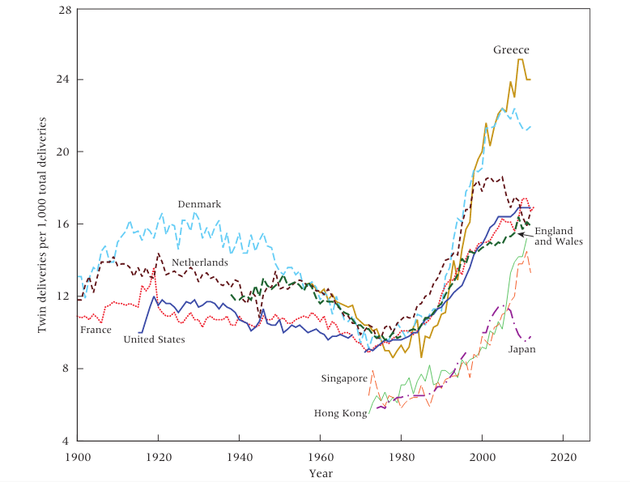

In 1975, there were 9.5 twin births per 1,000 deliveries in the United States. In 2011, there were 16.9 twins per 1,000 births. The increase over that time was similar in England and Wales (from 9.9 to 16.1), France (9.3 to 17.4), and Germany (9.2 to 17.2), and a little steeper in Denmark (9.6 to 21.2) and South Korea (5 to 14.6).

This rise is pretty much entirely from fraternal twins—two eggs released during ovulation and fertilized by two different sperm. The rate of identical twins, who develop from one zygote that splits and forms two embryos, tends to stay relatively constant around the world, and doesn’t seem to be affected by any external factors. But the likelihood of having fraternal twins, or dizygotic twins, changes depending on the age of the mother, how many children she’s already had, the country she lives in, and genetic factors.

Twin Rate in Developed Countries, 1900 to 2013

The older the mother, the more likely she is to have fraternal twins. This is one reason the study cites for the increase of twins in wealthy, developed countries, where women are more likely to have their first child later in life. In the United States, the average age of first-time motherhood was 26.3 in 2014, compared to 24.9 in 2000. In other countries, particularly in Europe and Southeast Asia, the average age is even older—Greece holds the top spot at 31.2, according to the Central Intelligence Agency’s World Factbook.

The other reason for the twincrease in the developed world is the proliferation of fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization and ovarian stimulation, which increase a woman’s chance of a multiple pregnancy. Ovarian stimulation can cause multiple eggs to be released at a time; during in vitro fertilization, a doctor may transfer more than one embryo to the patient’s uterus, to maximize the chances of a successful pregnancy. But that also means there’s a possibility that more than one embryo will take.

Twin rates in the developing world have been more stagnant. A 2011 study of 76 developing countries published in PLOS One found that in Asia and Latin America, twin rates are generally low, below 10 per 1,000 births, while mothers in Central African countries have rates above 18 per 1,000. Vietnam was the country with the fewest twins (6.2 per 1,000 births) and Benin was the country with the most (27.9 per 1,000). Over time, some of these developing countries saw increases in twins, but some saw decreases and some stayed the same, with any changes tending to be small. “The lack of an increase comparable to that experienced in high-income countries over the last decades suggests that the influence of fertility treatments is still low in these countries,” the study reads.

In some places, the role of fertility treatments may be waning. In about a quarter of the developed countries analyzed in the recent study—including Japan, Australia, Sweden, and Denmark, among others—the twin rate peaked sometime between 1998 and 2010 and then began to decline again. This is likely because, in response to the high multiple-birth rates that come along with fertility treatments, best practices began to shift toward only transferring one embryo at a time. Multiple pregnancies are riskier both for the mother and the children. But in many countries, this was not enough to compensate for the continued popularity of these treatments, and the increase in older mothers.

When the researchers examined childbearing age and fertility treatments separately, they found that, though it varied by country, the effect of fertility treatments was on average “about three times greater than the effect of delayed childbearing.” But, in real life these things aren’t completely separate—some women get fertility treatments because they want to conceive at a later age, when it may be more difficult to do so. And if this tangle of reproductive trends catches on in developing countries, there may be some doubly sleepless nights in store for parents around the world. Especially in Benin.