This is an edition of Up for Debate, a newsletter by Conor Friedersdorf. On Wednesdays, he rounds up timely conversations and solicits reader responses to one thought-provoking question. Later, he publishes some thoughtful replies. Sign up for the newsletter here.

Question of the Week

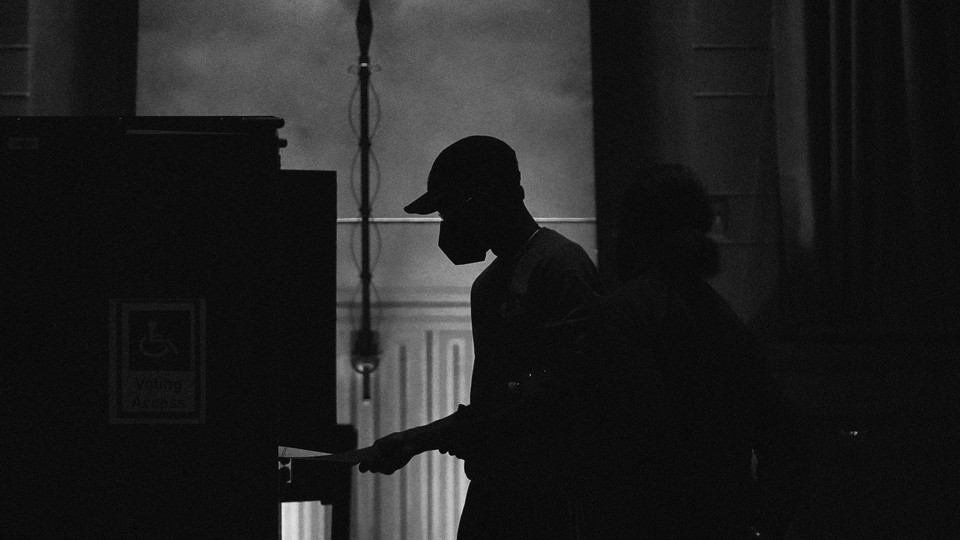

Elections alter the balance of power in a democracy while affording us new information about what voters want. What do you think about yesterday’s results and those still outstanding? Feel free to comment on federal, state, or local races, or any ballot initiatives, especially if what you’re seeing or thinking isn’t reflected by what you see in the media.

Send your responses to conor@theatlantic.com or simply reply to this email.

Conversations of Note

It’s too early for conclusive analysis of the midterms, with ballots still being counted in some races and observers just beginning to refine their analysis. But as ever, the Atlantic staff writer David A. Graham offers a compelling first draft of postelection history. His summary of where U.S. politics seems to be right now:

The final balance of power in the U.S. Congress and state houses won’t be clear for days or in some cases possibly weeks, but early results suggest that Republicans will likely retake control of the House, while the balance in the Senate remains too early to predict. GOP gains on Capitol Hill are the most important headline in immediate policy terms, since they mean President Joe Biden will be unable to move his priorities through Congress and will face new investigations … But the first round of results also suggests a smaller Republican victory than expected, and certainly smaller than some of the party’s leaders had at times predicted. This may prove the best midterm performance by the sitting president’s party since 2002. Several factors might explain that underperformance, including weak candidates, backlash to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs overturning abortion rights, and continued anger at former President Donald Trump.

At Politico, David Siders explained the conventional wisdom that Tuesday was a bad day for Trump:

If not for the former president’s interventions, the night could have been a lot better for the GOP. Just look at how the most Trump-y candidates fared in states where more traditionalist Republicans were on the same ballot. In Georgia, Herschel Walker was locked in a neck-and-neck contest with Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock. Gov. Brian Kemp, whose resistance to overturning the 2020 results infuriated Trump, easily defeated his Democratic opponent, Stacey Abrams. In New Hampshire, Republican Don Bolduc lost to Sen. Maggie Hassan in a race that didn’t even look close, while Gov. Chris Sununu, who once referred to Trump as “fucking crazy,” cruised to reelection.

Trump’s preferred candidate in Ohio, J.D. Vance, did better, beating Democratic Rep. Tim Ryan by a comfortable margin in that state’s U.S. Senate race. But he came nowhere close to the margin that incumbent Gov. Mike DeWine, a more traditionalist Republican, put up. In Arizona, it was still early, with only about half of the expected vote in. But Kari Lake was running behind Katie Hobbs. Even if she comes back to win, it will be a closer race than political professionals of both parties had predicted had a more traditionalist Republican, Karrin Taylor Robson, made it through.

And in Florida, Trump’s home state?

Ron DeSantis, the Republican governor of Florida — and a potential rival to Trump — won reelection in a 20-point landslide. In 2020, Trump carried the state by just more than 3 percentage points.

The results are good news for Republicans who want DeSantis to be their standard-bearer in 2024, Ross Douthat argues, because it vindicates their theory of what he could do for GOP prospects:

That theory, basically, is that there’s a decisive right-of-center majority there for the taking in American politics, an opportunity magnified by the Biden administration’s unpopularity. It’s a majority that Donald Trump pushed the party toward, by picking up working-class white voters in 2016 and then Hispanic voters in 2020 — proving that the G.O.P. coalition could be more blue collar and multiracial than its Romney-Ryan iteration …

But Trump himself is just too much, too erratic and polarizing and plainly dangerous, to complete the realignment on his own. And his influence on the party as a whole, manifest in the underperforming candidates he elevated in this cycle, is preventing the new G.O.P. majority from taking its natural shape. States like Pennsylvania, Arizona, Georgia and maybe even New Hampshire should have been easy Republican pickups; all they needed was a normal set of Senate nominees. Instead they got the kind of nominees Trump wanted, and the result is difficulty, defeat, disappointment and votes being counted late into the night.

Crucially, the DeSantis theory emphasizes, “normal” doesn’t have to mean “squishy.” Instead, his sweeping success in Florida proves that you can be an avatar of cultural conservatism, a warrior against the liberal media and Dr. Anthony Fauci, a politician ready to pick a fight with Disney if that’s what the circumstances require. You just also have to be competent, calculating, aware of public opinion as you pick your fights and capable of bipartisanship and steady leadership in a crisis. The basic Trump combination, cultural pugilism and relative economic moderation, can work wonders politically; it just has to be reproduced in a politician who conspicuously knows what he’s doing, and who conspicuously isn’t Donald Trump.

Speaking of Florida, is it still a swing state?

In National Review, Charles C. W. Cooke argues that, gradually and then suddenly, it became a red state:

For 30 years, Florida has been tough for the Democrats: The Sunshine State has not elected a Democratic governor since 1998; it has not elected a Democratic legislature since 1994; the last year in which a Senate or presidential candidate won here was 2012; and, in 2018, the only Democrat elected statewide was that lunatic, Nikki Fried. But, while Republicans have tended to win here, they’ve tended to win in nail-biters. Despite Republican waves in the rest of the country, the GOP prevailed in the Florida governor’s races by just 1 percent in 2014 and 1.2 percent in 2010. In 2016, Trump eked out a win by 1.2 percent. In 2020, that number was 3.4 percent. Four years ago, in races that both went to mandatory recounts, Ron DeSantis won the gubernatorial contest by 30,000 votes and Rick Scott won the Senate race by just 10,000. Between 1992 and 2016, voters in Florida filled in 48,263,173 presidential-election ballots. In that time, the difference between the Republican votes and the Democratic votes was just 17,753 — or 0.0004 percentage points of the total. Those 17,753 went to the Democrats.

Now? Something has changed. No longer can Florida be seen as a swing state. This is Republican ground. Tuesday night, Ron DeSantis blew out Charlie Crist by 19 points … and counting. This feat was echoed by Marco Rubio, who won by 16; by the Republican candidates for attorney general, chief financial officer, and agriculture commissioner, who all won by ten points or more; in the state legislature, which seems likely to feature Republican supermajorities in both chambers; and by the Republican candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives, who won 20 of their 27 races. For the first time in a long time, Republicans didn’t just win in Florida; they won big in Florida.

Failing Upward

The Atlantic’s Jacob Stern argues that Beto O’Rourke and Stacey Abrams have something in common:

The two Democrats are among the country’s best-known political figures, better known than almost any sitting governor or U.S. senator. And they have become so well known not by winning big elections but by losing them. Both Abrams and O’Rourke have won some elections, but their name recognition far surpasses their electoral accomplishments. After serving 10 years in the Georgia House of Representatives, Abrams rose to prominence in 2018, when she ran unsuccessfully for the governorship. O’Rourke served three terms as a Texas congressman before running unsuccessfully for the Senate, then the presidency. And they are both running again this year, Abrams for governor of Georgia, O’Rourke for governor of Texas. They are perhaps the two greatest exponents of a peculiar phenomenon in American politics: that of the superstar loser.

Who Is to Blame for the State of the GOP?

Jamelle Bouie indicts Republicans for their choices:

We are moral agents, responsible for our decisions, even if we can’t fully escape the matrix in which we make them. And yet so much of the conversation about the modern Republican Party assumes the opposite: that Republican politicians are impossibly bound to the needs and desires of their coalition and unable to resist its demands. Many — too many — political observers speak as if Republican leaders and officials had no choice but to accept Donald Trump into the fold, no choice but to apologize for his every transgression, no choice but to humor his attempt to overturn the result of the 2020 presidential election and now no choice but to embrace election-denying candidates around the country. But that’s nonsense. For all the pressures of the base, for all the fear of Trump and his gift for ridicule, for all the demands of the donor class, it is also true that at every turn, Republicans in Washington and elsewhere have made an active and affirmative choice to embrace the worst elements of their party — and jettison the norms and values that make democracy work — for the sake of their narrow political and ideological objectives.

How Democrats Lost the Working Class

In The American Prospect, the Democratic pollster Stanley Greenberg explains at length where the party went wrong. Ruy Teixeira has more at The Atlantic:

This year, Democrats have chosen to run a campaign focused on three things: abortion rights, gun control, and safeguarding democracy—issues with strong appeal to socially liberal, college-educated voters. But these issues have much less appeal to working-class voters. They are instead focused on the economy, inflation, and crime, and they are skeptical of the Democratic Party’s performance in all three realms. This inattentiveness to working-class concerns is not peculiar to the present election. The roots of the Democrats’ struggles go back at least as far as Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign in 2016, and, as important, to the way in which many Democrats chose to interpret her defeat. Those mistakes, compounded over subsequent election cycles and amplified by vocal activists, now threaten to deliver another stinging disappointment for the Democratic Party. But until Democrats are prepared to grapple honestly with the sources of their electoral struggles, that streak is unlikely to end.

Why a Perennial Swing Voter Went Republican in 2022

Andrew Sullivan explains at UnHerd:

There was no choice in 2020, given Trump. I understand that. If he runs again, we’ll have no choice one more time. And, more than most, I am aware of the profound threat to democratic legitimacy that the election-denying GOP core now represents. But that’s precisely why we need to send the Dems a message this week, before it really is too late.

By “we”, I mean anyone not committed to the hard-Left agenda Biden has relentlessly pursued since taking office. In my view, he and his media mouthpieces have tragically enabled the far Right over the past two years far more than they’ve hurt them. I hoped in 2020 that after a clear but modest win, with simultaneous gains for the GOP in the House and a fluke tie in the Senate, Biden would grasp a chance to capture the sane middle, isolating the far Right. After the horror of January 6, the opportunity beckoned ever more directly.

And yet … in return for centrists’ and moderates’ support, Biden effectively told us to get lost. He championed the entire far-Left agenda: the biggest expansion in government since LBJ; a massive stimulus that, in a period of supply constraints, fueled durable inflation; a second welfare stimulus was also planned — which would have made inflation even worse; record rates of mass migration, and no end in sight; a policy of almost no legal restrictions on abortion (with public funding as well!); the replacement of biological sex with postmodern “genders”; the imposition of critical race theory in high schools and critical queer theory in kindergarten; an attack on welfare reform; “equity” hiring across the federal government; plans to regulate media “disinformation”; fast-track sex-changes for minors; next-to-no due process in college sex-harassment proceedings; and on and on it went. Even the policy most popular with the centre — the infrastructure bill — was instantly conditioned on an attempt to massively expand the welfare state. What on earth in this agenda was there for anyone in the centre?

Whither California?

Apropos news that at least 352 companies have moved their headquarters out of the Golden State in the past few years, the Las Vegas Review-Journal published an editorial addressed to Nevada Democrats:

California is the most populous state and has the third-biggest land area in the union. It has a strong system of higher education and ample access to ports for international shipping. Plus, the weather, diverse terrain and beaches are superb. But California ranks just 16th in new capital projects. Per-capita, it ranks 46th, which is tied with North Dakota. On the per-capita list, Nevada ranks 35th. This didn’t happen by accident. California progressives have enacted policy after policy that make it hard to do business there. The taxes are high. The regulations are oppressive. The permitting is costly. The Small Business & Entrepreneurship Council ranks California as the 49th-most “entrepreneur-friendly” state. Laws stack the deck against employers targeted by trial lawyers. Energy is expensive. The possibility of blackouts is a regular occurrence.

… Unsurprisingly, companies have generally moved to states that are much more business-friendly. Workers are better able to afford houses and fill their gas tanks, even if the weather isn’t as pleasant. There’s an important lesson here for Nevada Democrats — and voters. California isn’t a model to imitate, but a slow-motion disaster to avoid.

My feature-length thoughts on the California dream are here.

Provocation of the Week

At UnHerd, Elbridge Colby argues that a change in America’s foreign-policy posture is urgently needed:

The United States is struggling to keep up with the military advances China is making to prepare for a conflict in the Western Pacific — the most plausible locus of such a war. Indeed, many of the most respected voices on US defence matters openly question whether the United States would prevail in a conflict with China centered on Taiwan. And … Washington does not appear to be taking the kind of dramatic steps needed to match China’s ongoing military buildup … As the Biden Administration made clear in its 2022 National Defense Strategy, the United States does not have the capacity to fight both such an exceptionally stressing war with China and another significant conflict, such as in Europe against Russia or the Middle East against Iran, on even roughly concurrent timelines. This military scarcity confronting the United States is felt not so much in overall number of soldiers or total expenditures, but rather in the critical platforms, weapons, and enablers that are the key sources of advantage in modern warfare — heavy bombers, attack submarines, sea and airlift, logistics, and precision munitions. It is not clear America has enough systems just to win a war against China alone.

His advice:

America should laser-focus its military on Asia, reducing its level of forces and expenditures in Europe. This will allow America to hopefully deter and, if necessary, defeat a Chinese attack on Taiwan and other US allies in the region, using military force to defeat Chinese aggression rather than substantially relying on economic warfare.

… Europe should focus on taking the lead on Ukraine and, more broadly, assuming the primary role in its own conventional defence. In this model, the United States can continue to provide more focused military contributions and support to Nato, but only consistent with a genuine prioritisation of the first island chain necessary to ensure prevailing there against Chinese attack.

That’s all for this week––see you on Monday.