The Dark Pageant of the NFL

If football is about to undergo some hint of a reckoning, it will be only partial.

Like millions of people, I had been looking forward to my weekly escapist fix of NFL Monday Night Football. Buffalo at Cincinnati promised to be a powerhouse clash between two teams with Super Bowl aspirations. No doubt this would be one of the top-rated television shows of the week in America, from the entertainment juggernaut that accounted for 22 of the 25 most watched prime-time telecasts in 2022.

I happened to miss the first few minutes of the contest while I walked to the market to buy a pint of ice cream. But whatever, it was all part of football’s grand entertainment bargain: I could get fat for a few hours on the couch while the players did all the work, provided all the spectacle, and suffered all the damage.

On Monday night, that damage fell heavily upon Damar Hamlin, a 24-year-old safety for the Bills whom few fans outside Buffalo had heard of before this week. Just before 9 p.m., Hamlin became football’s most dreaded kind of household name when he suffered cardiac arrest and collapsed on the field after tackling Cincinnati’s Tee Higgins.

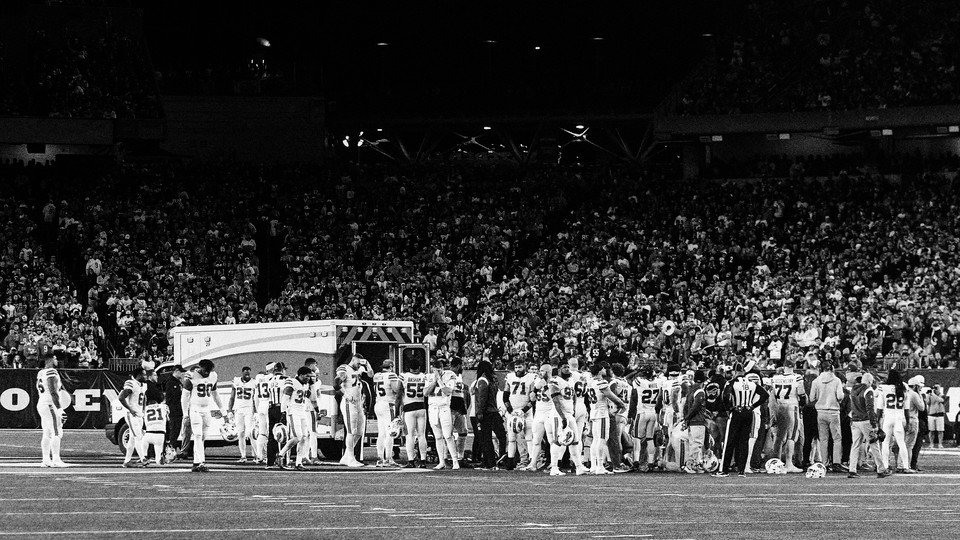

Silence in a football stadium is an immediate sign of trouble. You can tell that something’s not right when you turn on a game and see stillness in the stands and especially on the field. Was something amiss with the audio? The announcers barely spoke. When they did, ESPN’s Joe Buck and Troy Aikman seemed haunted, devoid of their usual game-day authority. The field sounded like a funeral. God forbid.

In the hours since Hamlin’s hospitalization (he remains in critical condition as of this writing), every gridiron commentator has pounded us with reminders of how unimportant America’s most beloved blood sport really is, in the scheme of things. They are right, of course. Football is not life or death—or it shouldn’t be. But watching the response to Hamlin’s injury, I can’t help but think that if the sport is about to undergo some hint of a reckoning, it will be only partial. Football was why we were all watching in the first place, and why this was so chilling: To separate the game from its danger would be impossible, much as it’s attempted.

Every player and fan of the sport is mindful of football’s mostly unspoken terror scenario, the one that played out Monday night near the 50-yard line of Cincinnati’s Paycor Stadium. But we are also protective of the reprieve the game gives us, and the league is here for this. “We offer a respite” was how Jerry Jones, the Dallas Cowboys owner, explained pro football’s essential promise to me a few years ago when I was researching a book about the modern super-sport, Big Game: The NFL in Dangerous Times. “We are a respite that moves you away from your trials and missteps, or my trials and missteps.” Putting aside the many “trials and missteps” that the NFL (and Jones) has made over the years, the value proposition he was describing is clear enough: Football has made itself America’s most inescapable reality show. They bring the action; we supply the blinders.

The existing arrangement is based on a few precarious concessions from heavy users like myself. It can be difficult for thoughtful fans of conscience (of course I’m one of those!) to luxuriate in the game without experiencing some pangs of moral dissonance over what exactly we’re watching. This season has taxed the boundaries of our escapism big-time. The Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa suffered multiple concussions, exhibited gruesome symptoms, and once again exposed the league’s inadequacy at protecting its players’ brains. New self-reporting from former players and research on dead ones shows that football continues to be a disastrous proposition for long-term health. Meanwhile, Hamlin is on a ventilator at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center, and there’s still a week to go in a regular season that the league last year expanded to 17 games.

NFL fans like to remind themselves that the players are well paid and know exactly what they’ve signed up for. Even Tom Brady, who is still throwing darts for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers at age 45, has compared playing football to “getting into a car crash every Sunday—a scheduled car crash.” If you count his high-school days, Brady has now endured three full decades of scheduled car crashes, and can’t seem to quit them. So, yeah, he knows what he’s risking, and Bucs fans presumably love what they’re still getting from the GOAT, who has managed to avoid serious injury except for a mangled knee that cost him his 2008 season.

Fortunately, in most cases, the injured players get up, usually under their own power. In serious cases, they are carted off, to the blanketing silence of the crowd. It is scary. But even then, the guy being wheeled off usually comforts us with a thumbs-up or some other sign that he’s at least alive and moving. It is a gesture of permission for his teammates to get on with their pulverizing, and a signal to everyone that another unthinkable blow has been dodged in a brutal game. Pass the pizza.

That’s what was so terrifying about Buffalo at Cincinnati, Week 17. Hamlin was not moving. There were no “encouraging signs” or thumbs-ups or pats on the helmet from his teammates as he was wheeled off. Damn, he was ambulanced off. I’d never heard announcers’ voices at those shaken octaves before, or a packed stadium so quiet. I’d never seen large groups of players sobbing on the field. The usual cognitive space we inhabit as football consumers became more uncomfortable. So much for not having to digest anything too gruesome with our snacks.

Suddenly, the big “existential” questions about football that we prefer not to think too hard about came crashing through our blockades of denial: Should a civilized culture really be sanctioning this? Can a game played by men of such size and speed ever be safe?

Yes, pro football has big and intractable problems, which continue to be no match for the general doltishness of the league office and the misfit billionaires who run and own the cartel. But based on my exploration of pro football, my best guess is that the game will survive despite the psychic and physical price it continues to exact. It has endured many “crisis” points over the past half century. The sport’s concoction of violence, strategy, and artistry perfectly suits the American mindset; nothing else comes close.

Even the horror of Monday night was itself a spectacle. No one had tuned in for this, obviously, but from what I could tell, not a lot of people were turning away or leaving the stadium, either. The game, in its ghastly suspension, became its own shared observance. How to proceed? Who is Damar Hamlin—the man, not the player? Pray for him.

And that, in a way that surprised me, was uplifting. Alongside the tragedy was a powerful display of humanity—the idea that somehow the sport could incorporate mature grief into its fun. The “insiders” charged with explaining the tragedy—especially the former players—seemed to be speaking more directly about the brutality we had all just witnessed, and surely would again. For a while, a more honest reckoning felt closer than it had when the night began.

“We forget that part of living this dream is putting your life at risk,” said ESPN’s Ryan Clark, a longtime safety in the league, whose raw and eloquent commentary served as an essential companion and conscience to the vigil. “Tonight, we got to see a side of football that is extremely ugly … The next time we get upset at our favorite fantasy player, or we’re upset that the guy on our team doesn’t make the play, and we’re saying he’s worthless, and we’re saying ‘You get to make all this money,’ we should remember that these men are putting their lives on the line.”

Another graceful aspect of the broadcast: The network showed minimal replays of the hit that felled Hamlin. This underscored how ordinary the play was. It was not dirty or illegal or immediately grisly, until Hamlin rose to his feet afterward and quickly collapsed. It could have been any of dozens of hits that occur in the course of a game.

From that point, teammates surrounded the injured player as first responders worked to revive him. The image of Bills and Bengals forming a wall around Hamlin, their partner in sacrifice, was itself a statement. The players were looking after one another, because who else was going to? Even if dire damage had been done, this was a gesture of brotherhood in a sport that offers them limited protection, much less respite.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.