This story was supported by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

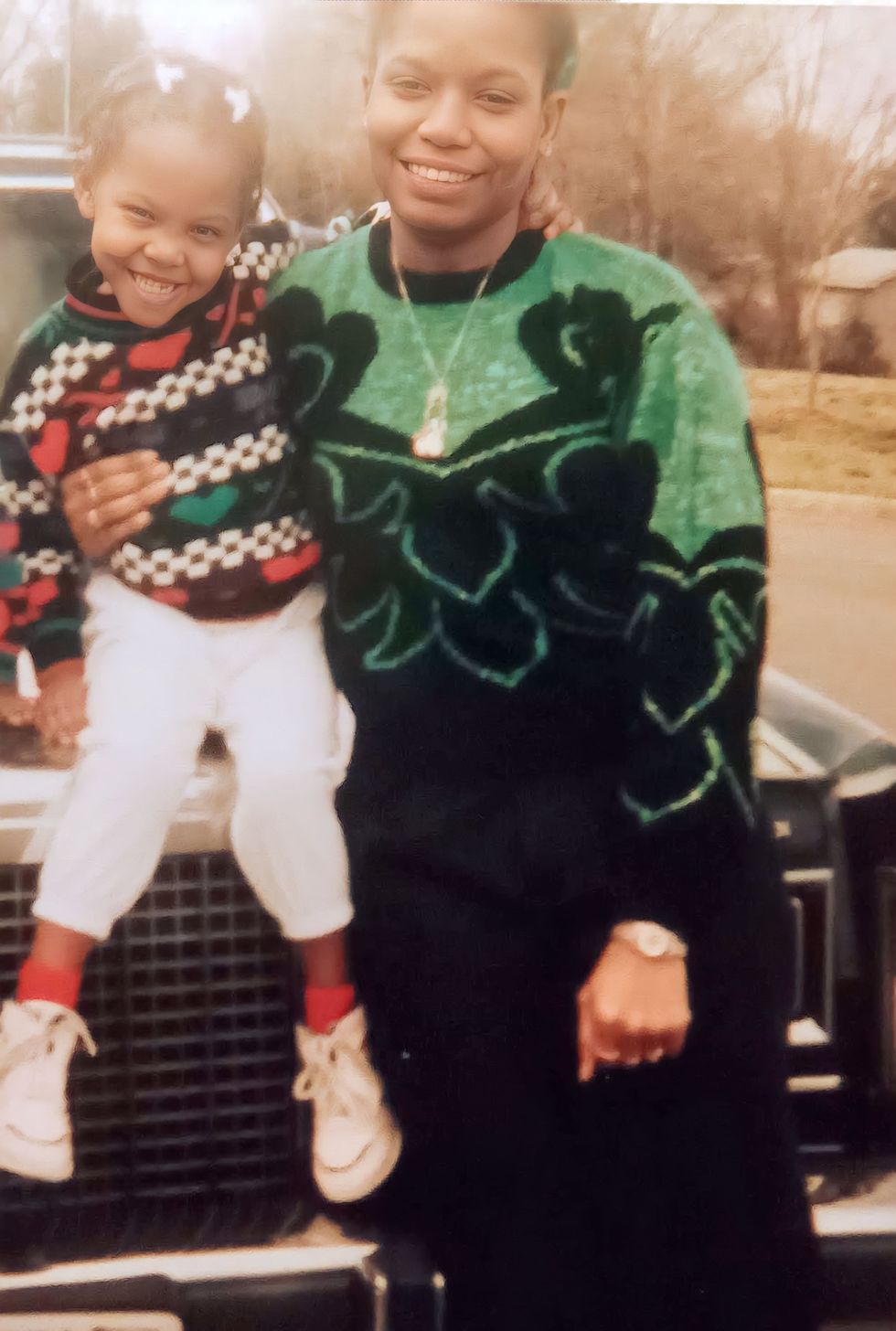

Marcus McKinley was a junior at Ohio University when his mother, Kim, then fifty-five, collapsed at work. He figured it was dehydration, but when he got to the hospital, he found out it was more serious than that; she’d had a stroke and needed brain surgery. Her right side was paralyzed, so she couldn’t walk, and when she first got out of the ICU, Marcus couldn’t understand a word she said. The weeks and months just after a stroke are the most important for rehabilitation, but Kim’s initial progress was minimal, and she languished. His mother had been gregarious and liked to go line dancing, or watch Browns and Buckeyes games. Before, she had a wide, warm smile, but now her face drooped.

For about a year, Kim’s fiancé did the physical work of caring for her while Marcus provided financial support from his part-time job at a tire factory and from a summer internship as a software engineer at a bank. But a couple of months after Marcus’s graduation, his mother’s fiancé called to tell Marcus he had to go out and then, when Marcus got to their house to lend a hand, told him he was leaving for good. After that, his mom’s fiancé only answered their phone calls once, to inform Marcus that he planned to stop paying his mother’s utility bills. Marcus realized he would have to step in.

It’s tempting to see Marcus and his mother as a sad, isolated story, a patch of bad luck that could befall anyone, but won’t befall most. After all, a debilitating stroke at fifty-five is rare; being a twenty-three-year-old shouldering that burden alone is even rarer. But caring for a family member with a long-term illness or disability is neither rare nor exceptional. Marcus is now one of the estimated fifty-three million family caregivers in the U.S., according to a 2020 study by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving. That means, as of 2020, more than one in six Americans was actively responsible for the daily needs and well-being of a loved one. That number only increased during the Covid-19 pandemic, as families took loved ones out of long-term care, adult day centers closed, and the paid caregiving workforce—burned out by greater risk of infection, poor treatment and work conditions, and paltry pay—decreased by as much as 12 percent in certain sectors.

Of those family caregivers, more than three million are members of Gen Z: young people born between 1997 and 2012, many of whom have not yet or just barely crested into adulthood and whose lives have been knocked sideways by a family member’s illness or disability. As our country ages and our paid-care workforce dwindles, the number of family caregivers is expected to grow. Although most caregivers have a job, about a third are forced to cut back on work, and one in nine stops working altogether. That in itself can be catastrophic: A study by MetLife found that the average boomer who leaves the workforce early to care for a family member sacrifices around $300,000 in lifetime earnings and retirement benefits. Although there is no direct research on the financial impact to Gen Z caregivers, one can presume the effect on lifetime earnings, especially for a long-term caregiver, is even more severe.

Marcus is a responsible, focused guy by nature. He didn’t drink or party in college. He didn’t date, either. He considered a girlfriend a kind of applicant for marriage; he would graduate with $90,000 in college loan debt, and he didn’t want to start a relationship until he was financially stable. Marcus came from a family where there wasn’t a lot of ambition or a lot of money in the bank: His mom worked as a dental hygienist and made a decent salary, but there was never much left over for savings. His dad, in theory, tried to teach good financial habits, by giving Marcus and each of his two siblings $20 for birthdays and other special occasions to put in a bank account, but then he’d often ask for it back. Marcus, though, had drive. He wanted savings. He wanted stability. He’d taken a career test in high school that had shown an aptitude for math and science, so he studied computer science, because he thought working in technology would guarantee a good salary. He didn’t like to take risks; he didn’t want trouble or circumstance to derail him.

Marcus’s brother and sister were in Columbus, just like him, but they had their own lives—his brother had a week-old baby when their mother’s stroke happened, and his house had stairs. Their father, who had divorced their mother when Marcus was a senior in high school, didn’t have a car or, sometimes, a place of his own to live. That left Marcus as his mother’s full-time caregiver. He moved her into his one-bedroom apartment in Columbus; for the next six months, he slept on the couch so she could have his bed.

Marcus did the best he could with what he knew. He used his software-development skills to build an app with pictograms to help his mother communicate her needs—toilet, meal, bed. He Googled what he needed to navigate the legal muddle to become his mother’s guardian. He had lived on his own for four months when his mother moved into his apartment—“four months to finally taste independence,” he wrote on Facebook.

Marcus became responsible for everything his mother required to get through her day. “I cook for her, clean, do laundry, put her in bed, help her get dressed, help her shower, take her to the bathroom, get her outside, manage her finances, take her to appointments—the list goes on,” he told me. “She can wipe; she just can’t get to the toilet.” He learned that his mother saved almost nothing for retirement, and he gets bills and calls from debt collectors all the time. Yet, in some ways, Marcus sees himself as fortunate: His mom has disability income and Medicaid, which covers the cost of an aide who comes to the house a couple of hours a day and delivery of two meals a day. His sister helps her shower so he doesn’t have to get too involved in what he calls the “feminine side of things.” He has a well-paying job, as a software developer for a bank, that went remote when the pandemic began. Still, there were nights he’d get up four or five times to take her to the bathroom. It was the broken sleep that got him the most. What he didn’t take into consideration, as he made arrangements to care for his mom, was his own mental health. Marcus estimates that there were times he took care of his mom nineteen hours a day, seven days a week—every hour that Medicaid wasn’t paying an aide to keep an eye on her. “You put it on paper and of course you can handle it,” he reasons. “I can handle it,” he repeats, as if willing it to be so—“but not really.”

I first started thinking about people like Marcus when I read about an organization called the American Association of Caregiving Youth. I learned that more than 1.4 million children under the age of eighteen take care of a sick or disabled family member. Then I learned that number is almost certainly an undercount. There is no systematic data collection on how many minors or young people care for family members. More recent estimates put the true number at anywhere from 3.4 million to 5.4 million when you include those who assist with caregiving. Young caregivers, who are often still in school and need parental care and nurturing of their own, handle all sorts of tasks for their families: shopping, cooking, cleaning, laundry, medication management. Most American health insurance plans, including Medicare, offer almost nothing for nonmedical long-term care at home—a fact that stuns many family members thrust into caregiving roles after a catastrophic event. The price tag for a year of in-home assistance is around $52,000 out of pocket; a year in a nursing facility averages $101,500. The vast majority of American families thus take the burden to provide care on themselves. This includes routine expenses—prescriptions, wheelchairs, retrofitting a home to make it accessible, personal-care items like incontinence supplies—that amount to $7,200 annually on average, as well as what the AARP estimates is $470 billion in unpaid care every year.

Abroad, that financial pressure on caregivers is not as acute as it is in the U.S., in part due to government support, a bigger safety net for long-term care, and more flexible work policies. In the UK, caregivers, especially those who reduce work hours to care for family members, are eligible for an allowance to make up for lost income. They are also eligible for respite services—paid caregivers who allow family caregivers to have time away—funded by the National Health Service. Youth caregivers have their own bill of rights, including a right to continue their education. Other countries, such as the Netherlands, Germany, Finland, and Taiwan, have compulsory and, depending on the country, publicly funded long-term-care insurance that helps cover the cost of paid caregivers, including in the home, for both medical and nonmedical services—everything from cleaning to preparing meals and doing laundry. In Germany, full-time employees who take time off to care for a family member can borrow against future wages to reduce their work hours for up to two years while retaining their position and their income. Such programs and services make our system—with no guaranteed paid family leave, no financial support for caregivers who forgo wages, and few options for in-home care that isn’t paid for out of pocket—seem especially paltry.

When families are the primary caregivers for our nation’s sick and disabled, logic dictates that kids and young adults must get involved. Although illness and disability affect people across the class spectrum, many of the kids most involved in their loved ones’ care come from low-income, single-parent households, and they often struggle in school, suffer from sleep deprivation, and are tormented by depression, anxiety, and chronic stress. Who were these kids, I wondered, and why were we leaving them to contend with all of this on their own?

I met middle schoolers, teenagers, and young adults who took on caregiving responsibilities. There was Abby, the high school sophomore in Delray Beach who did the cooking, cleaning, and shopping, injected her mother’s insulin as well as bathed and dressed her, and took on shifts at a grocery store to help cover costs. There was Becca, who was six months pregnant when the adult day center her mother attended closed due to Covid, leaving Becca to contend with caring for a newborn and a woman with severe Alzheimer’s around the clock while also working full-time. There was Aisha, who left her full-time job at twenty-seven to care for her mother who had frontotemporal dementia; she intended to stay for six months, but eight years later, she was still living at home, also caring for her father, who’d had a stroke. There was Sarah, whose husband was diagnosed with ALS in his thirties and who had to fight for months to get the home health care his insurance entitled him to, even after her husband was completely paralyzed and placed permanently on a ventilator. (Despite his terminal condition, Sarah and her husband both still worked full-time for years, he by using a special eye-scanning computer to communicate—they needed the money.) There were Charlie and A.J., who were nine and eleven when they began to take care of their grandmother, who had Alzheimer’s, after school, and then, under the banner of an advocacy project called Kids Are Caregivers, Too, petitioned their Virginia school to give community-service credit to kids who take care of loved ones, to make up for the extracurricular activities they miss out on.

Every story challenged the image of the average caregiver as someone in late middle age, likely a woman, caring for her aging parents: stopping by after work to do laundry or cook dinner before eventually relenting and putting them in a nursing home. Each of these people described a fraught, frantic life in which they scrambled between responsibilities such as work, school, and relationships, were chronically sleep-deprived, made significant compromises about their education or career trajectories, fought against burnout, and found they simply had no other choice but to keep going.

Maija Penn was twenty when she got a call from the police. Her mother, commuting to her job at McDonald’s, had been pulled over for reckless driving; the officer initially thought she must be drunk. But once he approached the car, he realized that wasn’t it. Maija’s mother had what the family referred to as “a tic,” involuntary movements and tremors that made it hard for her to control the steering wheel. He told Maija (pronounced “Maya”) he wouldn’t give her mom a ticket if Maija promised to take her to the doctor.

A neurologist eventually diagnosed Maija’s mom with Huntington’s disease, an inherited condition that causes brain degeneration, immobility, and difficulties with all activities of daily living. Maija lived with her parents and her two sisters in Fredericksburg, Virginia, but Maija described the rest of her family as “in denial,” so she took control, booking appointments for her mom with local experts on Huntington’s to make sure her mom got the best care. Maija was the one who took away her mother’s car keys and arranged her own work schedule so she could shuttle her mother to her shifts at McDonald’s. Maija was left in charge of cleaning, cooking, administering medications, and, as her mother’s symptoms worsened, managing her mother’s incontinence and the increasingly disruptive psychiatric symptoms—paranoia, belligerence—that are part of Huntington’s progression.

She struggled to keep up with her classes. She was earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology and behavioral health and working at the same time as a behavioral technician for children with autism, helping them manage their symptoms and behavior. Maija had no benefits or paid time off. She took on more clients, juggling three jobs to pay her mom’s medical bills as well as tuition for her own college classes. “I was go go go, and when I had a moment to sit down and think, I would just be upset, or my mind would go a mile a minute. My focus was work, school, take care of Mom, repeat,” Maija tells me. She managed, on average, to work twenty or thirty hours a week—a feat on top of school and care responsibilities. Still, with her pay at $13.50 per hour, she earned a total of around $19,000 one year—far too little to cover her family’s expenses.

At the time, Maija was one of the several million caregivers in the U.S. who are also students, most of them pursuing college or advanced degrees. (After eight years, Maija finally completed her bachelor’s degree in May.) These students are late to class, or skip it altogether, or fall asleep in lecture; they are more apt to turn their assignments in late and fall behind. Other young caregivers’ educations stall out before they even truly start, a path that can have rippling financial effects: Putting college off for even a year can cost graduates up to $17,300 in savings, according to a report by Student Loan Hero. Even graduating from high school becomes more precarious when caregiving: A Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation study on high school dropouts found that 22 percent of dropouts nationwide cite caregiving as the reason for leaving school.

Feylyn Lewis, an independent social-work researcher who also serves as assistant dean of student affairs at Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, has shown that caregivers aged eighteen to twenty-four experience housing insecurity or problems paying bills who were also students were chronically late, had poor attendance and felt misunderstood by teachers and staff. Her research subjects consistently reported the same needs: I wish there were more support for the person I provide care for. I need money. I want someone to talk to.

John Adeniran, who is now twenty-five, at least got to finish college. He is the youngest of seven, the baby of a close-knit Philadelphia clan. In 2017, when John was nineteen, his mom, who had worked as a nanny for most of her life, was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, but she had already been showing symptoms for years. During his time at Dickinson College—where he studied computer science and neuroscience, led Bible study, and was named student leader of the year—two of his sisters worked opposite shifts so they could take turns watching their mom twenty-four hours a day. John did his best to sub out his siblings when he could, devoting his school breaks to his mother’s care.

In 2019, his mother’s dementia had progressed to what the doctors call a moderate-to-severe level, so even though she still recognized John and his siblings, she began to need around-the-clock supervision to make sure she didn’t wander off or use the stove. When John graduated, he put off thinking about graduate school and getting the kind of job he wanted, which would have required him to be out of the house, to become his mother’s full-time caregiver. He took a job as a “social listening analyst”—monitoring social media and using data analytics to provide consumer reports—that allowed him to work the second shift, from 2:00 to 11:00 p.m., so he could attend to his mom most of the day.

John is still able to work full-time, but it’s a tough schedule: “I’m dividing my attention between two things,” he says, something I heard echoed in many of my conversations with caregivers. “That means there’s some dip in the ability for me to provide completely dignified care for my mom, which I don’t particularly like.” He has had to take out loans to cover costs—bills at home, insurance, and his mom’s medical bills, prescriptions, and supplements.

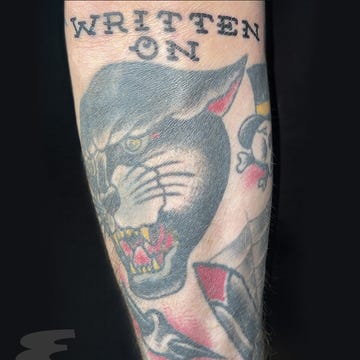

John has a soulful side and talks about his caregiving not as a family responsibility but as a vocation. He keeps a vision journal. He refers to filial piety, to the opportunity for growth that caregiving brings. Two sociologists, Leonard I. Pearlin and Marilyn McKean Skaff, have written that caregiving can be described as an “unexpected career”: Although it is a common experience, it’s not typically one that people anticipate. “The very fact that it entails circumstances for which people are unprepared may itself be a source of distress,” they write. But not for John: “I knew I’d be able to become someone who would be able to provide that care,” he tells me.

His experience with his mother has motivated him to become an advocate: From 2019 to 2021, he was a fellow with Caring Across Generations, an organization co-founded by MacArthur fellow Ai-jen Poo to improve family-caregiving policy. As a fellow, John advocated for more home- and community-based resources for people who require care and worked on get-out-the-vote drives to elect officials, like President Joe Biden, who campaigned on more supportive policies for caregivers, including expanding access to long-term care at home, creating a national paid family leave program, and allowing families a tax break based on care expenses. And although Biden’s administration allotted $460 million to home- and community-based services, none of the policies that he campaigned on that would have signaled a sea change in how we support caregivers, ended up in Biden’s signature legislative packages.

Beyond his advocacy work, John likes to read and keeps an intermittent blog, where he describes himself as a “wannabe pan-African Kierkegaard.” In the afternoons, while he’s working, he tries to keep his mom engaged with music. He made a playlist of songs she might hum or murmur—her favorite Nigerian songs from her youth, like those of King Sunny Adé, along with gospel, jazz, and old-school R&B—and he likes to take breaks from work to dance with her. “I do try to make sure that I’m a good companion,” he says.

John’s family has had only minimal outside help. Early in the pandemic, it felt too risky to bring someone in who might transmit germs to his mom, who couldn’t understand why she had to wear a mask. Plus, the cost was a hindrance: Medicaid will sometimes pay for an in-home aide, but only under specific circumstances. To qualify for Medicaid, many families must spend down their assets to less than $2,000, but even then, not all care is covered. (John says that there was no need for his family to spend down—“we were poor enough,” he says, laughing.) Medicaid has a bias toward institutions: Although the government would likely cover care for John’s mom if she were in a nursing home, the program is not required pay for expenses at home or in the community, such as a nonmedical home aide or an elder day program. Each state has its own rules for who is eligible for community-based care, but each applicant must be screened, and there are more than 16,000 people on the waiting list in Pennsylvania. Those on the list can expect to wait seven years or more before receiving services—what can feel like a lifetime when you're providing care without support, or an eternity when you’re still basically just a kid.

John has almost no time for himself, and time dictates everything in his life. He falls victim to what he calls “revenge procrastination”: sacrificing sleep for leisure time, so he can “regain control or equilibrium.” “When I think about the night, it feels like an open landscape, but it’s also ephemeral,” he tells me. He only has from 11:00 p.m. until 6:00 a.m. to sleep, respond to text messages, pay bills, do household chores, or do something for himself: read, write, watch TV. He can’t often sleep through the night anyway because his mom gets up to go to the bathroom, or she’ll wander around and John will need to direct her back to bed. John studied neuroscience, so he knows that, given his mom’s condition, he is at risk for early-onset dementia. He knows, too, that his current lifestyle—working until 11:00, getting up early or staying up late to get a few minutes to himself, not exercising enough, forgoing doctor’s appointments—isn’t good for his health. If his health is decent, it’s because he’s still young, he says—a speculation that’s borne out by research, which shows that chronic stress renders caregivers’ health consistently worse than that of their peers. But, he says, “care is king, and I put it above all things.”

When he was in college, Marcus lived in a house where social gatherings happened naturally. Friends would come over to watch movies, or they’d all go to the football field and play soccer there. That life ended abruptly. His college friends scattered around the country, and, for the first two years after his mother’s stroke, he was rarely able to join the few who were local when they went to a bar to hang out. At college, he had put off building a social life until he was on a financially stable path, and now he’s not sure how that will ever be possible. “The worst part,” he says, “is not seeing how to free up more time for myself and feeling like I am missing out on my opportunity for independence.” The weekends are the loneliest: “I watch all of my friends and acquaintances doing what they want on their time and it’s a hard thing to look at. That’s mostly when I start to think with this situation, When will I ever be free again?” If he does go out, his brother or sister must cover for him, and he gets text messages asking when he will be back. “I’m not there but I’m still there,” he says.

Sometimes, when his mom isn’t in a cooperative mood—if she doesn’t want to do her physical therapy exercises or won’t make the effort to say words like “bathroom” properly and rolls her eyes at her son’s corrections—Marcus stews. His mom’s hypertension preceded her stroke, and he suspects that her choice not to take her prescribed medication may have led to it. She has led a sedentary life, and she used to drink almost daily. It makes him angry. If only his mother had made better decisions. “Whenever I do think about the situation, I’m like, It really didn’t have to be this way.” He tries to remember where she came from—a tough neighborhood in Cleveland, with her own struggles growing up—because “I don’t want to be as mad as I can get.”

What troubles Marcus the most is how long this version of his life could go on. His mother is now just fifty-nine and, despite everything, relatively healthy. He realizes that unless he puts his mom in a nursing home, this could be his life for the next twenty or thirty years. “That was a tough pill to swallow,” he tells me.

As Lewis, the independent social-work researcher, has written, young caregivers are preoccupied with providing for others at a time when, developmentally, they are meant to be defining their identities, building relationships outside the family, and making decisions about educational and career paths. It’s the time when you try to become the person you want to be, the person you feel yourself to be inside. But how do you do that between taking trips to the bathroom with your mother? How do you do it only between 11:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m.? How do you do it when you never see your friends, or can never act twenty-three? When you’re so alone and you don’t know when it will end? Caregiving in your teens and twenties is what sociologists call an “off-time event,” a normal human experience that comes at a point in your life when it’s not normal. No one may ever be prepared for caregiving, but doing it at a young age can feel more jarring because there’s a sense of being out of sync with your peers.

The fact that Marcus’s situation appears unusual, and how it limits others’ ability to empathize, frustrates him. His brother, who has two children, will tell Marcus he knows what Marcus is going through because he can’t get away from his kids. “I’m instantly thinking, You chose to have those kids. I guess it’s my choice that I don’t just throw my mom in a nursing home,” Marcus says. Pearlin and Skaff, the two sociologists who researched the stress of caregiving, refer to this as “role captivity” and remark that it often comes with a sense of loss, “including a feeling that ‘a caregiver’s identity is fading.’” Besides, Marcus thinks, with kids, “there’s a time limit.” By twelve, “they probably won’t want to be around you all the time,” and by eighteen, they’re not your problem anymore. It’s an oversimplification of parenting, for sure, but one a resentful twenty-something is entitled to make. Meanwhile, Marcus, who is now twenty-five, sees himself in thirty years still taking his mother to the bathroom.

“That comes with a major emotional toll,” says Jennifer Simpson, the former assistant director of youth and community activities at the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, who worked in that role with young people involved in caregiving. “We see that it’s not only the literal task they have to do for caregiving that’s burdensome, but there’s also the emotional burden of feeling like they can’t talk about it, it’s shameful, they’re alone.” Young caregivers tend to feel more mature than their peers: They are concerned about financial matters, life-or-death matters, when their peers are preoccupied with team sports or social cliques or college applications or first jobs.

Even if there are millions of young people saddled with these same worries, it doesn’t often feel that way to those going through it. Feylyn Lewis, the assistant dean of student affairs, who researches young caregivers, knows some of this from personal experience. When Lewis was eleven, her mother had spine surgery to address degenerative disk disease, but the surgeons took out the wrong bones in her neck, leaving her with chronic pain. Lewis and her brother cared for her from then on. Lewis recalls asking a therapist and social workers for books to read about what she and her brother were going through. “They would shake their heads and say no, we don’t know anyone like you at all,” she tells me.

To mitigate that loneliness, some young caregivers seek each other out, to share resources and to commiserate. As might be expected for an Internet-native generation, a lot of this takes place online. John, the Philadelphian whose mother has Alzheimer’s, feels a lot of guilt for being unavailable to friends from what he sometimes considers his former life, and he has found that his fellow-caregiver friends online are more able to empathize. “There’s a certain understanding, where you don’t need to really say anything,” he says. “There’s an acceptance—‘I know you had a really rough week. I know you were tired.’”

About a year into taking care of his mother full-time, Marcus, who takes care of his mother who had a stroke, joined a young caregivers’ group on Facebook. He sees a lot of posts in which peers write about feeling underappreciated by the person they’re caring for. Others pose the kinds of questions that seem obvious or naïve to the initiated: How in the world do you guys do this and work at the same time? Some feel resentful that, as adults, they are taking better care of their parents than their parents ever took of them. Or they feel they are compromising how they raise their own children in order to care for the parent who didn’t do such a hot job to begin with. They endure heartbreak over romances that fracture under the pressure of caregiving responsibilities, or lament that it’s nearly impossible to get into a relationship when you’re a full-time caregiver. They wonder whether to move in with parents who need care but also have substance-use disorders that trigger old traumas. Marcus tries to help: He tells them about his own experience asking for an accommodation to work part-time from home, something his company was willing to extend even after others returned to the office as the pandemic wore on, or warns them away from claiming their loved one as a dependent on their taxes, as it could short-circuit certain government assistance.

Shortly after joining the Facebook group, he posed his own tough question:“Do you feel like putting your loved one in a facility when you are ‘able’ to take care of them yourself is wrong?” He worried that his mother wouldn’t be happy in a facility. As much as he didn’t want to face down twenty years of caring for her, who could handle twenty years in an institution?

The responses were sympathetic and supportive. Many acknowledged that there’s a difference between being physically able to care and having the mental stamina to do so. Not everyone is cut out for this, one person wrote. Another wondered if it might actually improve Marcus’s relationship with his mother to no longer be her caregiver but to go back to being her son.

Marcus began caring for his mother before Covid-19, but the bulk of his time as her primary caregiver happened during those years of increased isolation and risk of infection. In some ways, the pandemic made Marcus’s life a little easier: He was able to work from home full-time so he could be there for his mother. But it added other stressors: fear of having outside help, due to the increased risk of exposure for his mother; extended periods of total social isolation; feeling like there was nowhere safe outside the house to get a break. For some caregivers, having their loved ones at home meant keeping their family members protected and accessible, but it also meant they were with their charges around the clock, with little or no assistance, for months at a time, working themselves to the point of total exhaustion. As everyone grappled with the mental toll of the pandemic, caregivers experienced mental health symptoms at more than twice the rate of people without those responsibilities.

For Marcus, three years into caring for his mother, some of that pressure has ebbed. He has an in-home aide for his mom once again, and he is back in the office a few days a week. In the last year, Marcus decided to focus on ways she might improve. He needed something to hope for. Two years is a long time after a stroke to try to regain basic skills, but Marcus had a feeling she could still make progress. She was still young, and her body was relatively strong. Insurance will cover physical, occupational, or speech therapy only when it seems like there’s potential for improvement, but his mom had plateaued, and with every passing week, it was harder to make the case. Still, every time he took her to the doctor, Marcus asked for more therapy. It was “like pulling teeth,” he says. But he persisted. “Put in the referral, please,” he’d say. “Give her a shot.”

When his mom finally got back into therapy, she was reluctant. She had grown accustomed to how things were, the therapy was mentally taxing, and trying and failing was frustrating and tedious. Repeating exercises whose sole outcome was making a better S sound “didn’t give her a big feeling of accomplishment,” Marcus says. Some days she didn’t want to bother. But Marcus was “very real with her.” This was likely her last chance, he told her. If she wasn’t going to walk again, he didn’t want it to be for lack of effort. “I had a lot of hard conversations with her.”

She started to make some headway—standing up on her own from her wheelchair, for example—and ultimately that demonstrable progress spurred her on. It spurred Marcus on, too. An avid gym-goer, Marcus knew how to engage the glutes to support his body weight. “Whenever she collapses, I can tell her, ‘Squeeze your glutes’ and she’ll pop right back up. It’s super empowering,” he says. “The moment you get into a situation like this, you assume you’re unqualified,” but it turns out “a lot of skills are transferable.” Within a month, she started standing up, walking short distances, getting herself to the bathroom alone. Now she’s much more independent. The only thing he reliably must do is help her put on a bra “because that’s a two-hand job.” She even microwaves her own food. “I’m able to get a full night of sleep now,” he tells me. Without that, he says, he would likely have started the process of putting her in a nursing home.

Around the time his mother was becoming more independent, their home health aide quit; the profession has high turnover because the work is so taxing and the wages so poor. The change could have been a disaster for Marcus—finding someone new when there’s a shortage of aides and training them without disrupting his own work—but because of his mom’s improvement it wasn’t that big of a deal. He’s confident enough in her abilities that he can still go to the office a few days a week. With the help of a cane, she walks up the stairs now, so he feels he can leave her alone for longer periods. “I am so proud of her,” he says. It makes his mom happy, too. “She loves that feeling of independence,” he tells me. She likes to tell him, “I don’t need you; go ahead, go.”

In the year since his mom started physical therapy again, things have changed remarkably for Marcus. He joined a church and attends every Sunday. He goes rock climbing and to the shooting range with friends; he took up jiujitsu. He has a social group he sees regularly for game night or just to go out to eat. He’s started dating, too. For a while he saw someone he knew in college who’d always had a thing for him; when that didn’t work out, he met someone else. In July, he went camping in the woods for a friend’s bachelor party; he was completely unreachable for four days. He made sure his brother checked in on their mom once a day, or sent food via DoorDash to be certain she was eating. It’s the kind of thing Marcus never could have imagined a year ago. “I’m liking the way things are trending right now,” he tells me.

Not everything is fixed. His mom still has residual cognitive defects. He’ll ask her to boil some eggs and “then I see a turkey getting deep-fried.” Driving is out of the question for her, and her speech hasn’t improved much. He takes her to the gym three or four evenings a week.

He knows he can’t go on like this forever, that “there’s a lot of life I haven’t lived.” But at the same time, “I feel obligated to make sure I keep her in an environment where she has the best ability to recover,” he says. Now that things are on a better trajectory, he doesn’t think about the nursing-home option as much anymore. “If she wants to keep working, I’ll keep working with her,” he says. Besides, he knows he can never go back to being just her son; too much has changed for each of them. But, Marcus says, he’s not interested in being a dictator. “There’s still that line of respect,” he says. “I want her to have an equal say in what happens.”