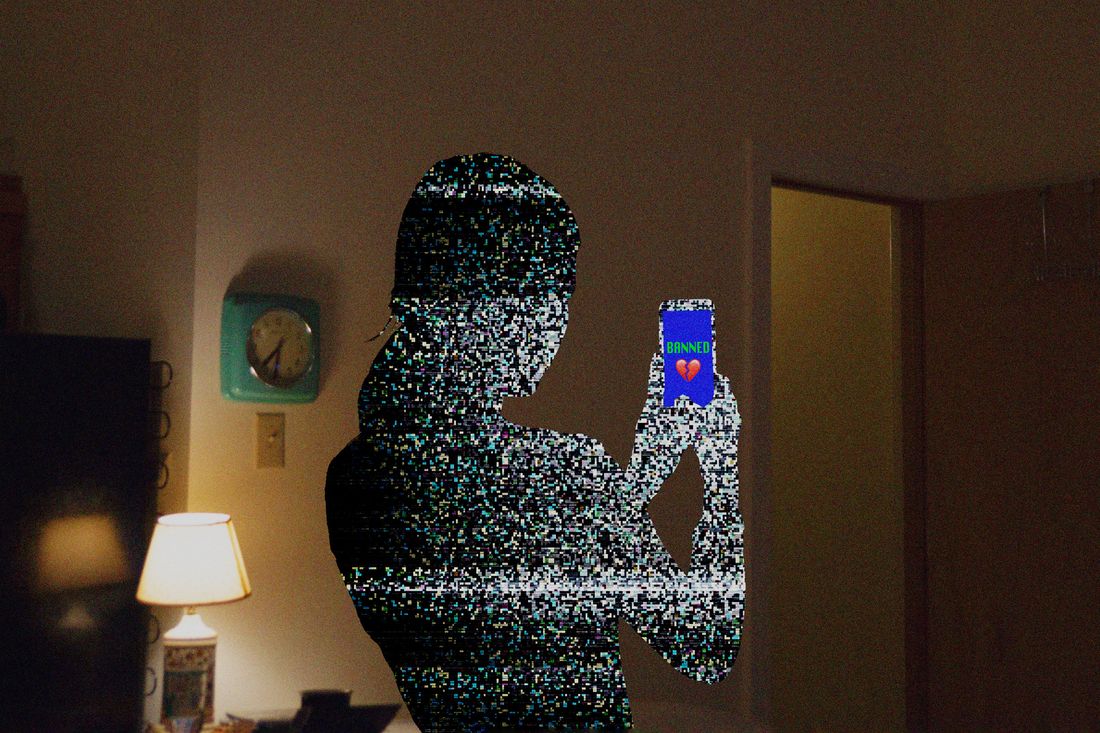

If Instagram is the podium where those who have won at love show off their medals — She said yes! So thrilled to embark on this homeowning journey together! We welcome baby boy Oscar! — then dating apps’ Better Business Bureau pages may be the dive bars where everyone else goes to drink away their sorrows. Every year, the BBB receives thousands of complaints, nearly all from people who believe they have been banned from the apps in error. The emotions expressed in these complaints often mirror bad breakups. There’s anger, particularly from users who are having difficulty securing refunds for paid subscriptions they can no longer use. There’s indignation, an insistence that there was some mistake or misunderstanding: “I’m a respectful person and I always respect the [word redacted by the BBB],” one exile said. Then comes pleading: “I’ve been a loyal and respectful user,” wrote one Hinge complainant named Michael. “Seeking to find the love of my life. Hinge is the best app for that. I’d love to be reinstated and have only the most honest and loving intentions.”

Almost everyone presents a theory for why they’ve been banned. Maybe their photos triggered the artificial intelligence designed to detect fake profiles; maybe they made and deleted profiles too many times in quick succession. But most complainers believe they have been the victims of “revenge reporting.” “I have confirmed that this was a personal vendetta from someone on the app to remove me permanently because I was not interested in seeing or talking to her again,” one user, banned from Hinge for violating the app’s terms of use, wrote to the BBB in June. The user claimed they had confronted the vendetta-holder, who confessed she had “had a moment of weakness and falsified a report because she was dissatisfied that I believed we were not compatible.” When a Hinge representative asked for documentation, the user said they could not provide any because the confrontation had occurred in person. “This account will remain banned. Thank you for your understanding. Sincerely, Hinge,” a representative replied.

Revenge reporting is distinct from reports due to discrimination (trans dating-app users, for example, are frequently and flagrantly misreported). When someone claims they have been revenge-reported, they typically mean one of three things: They were reported by a salty ex who stumbled upon their profile, they were reported in retaliation after having rejected another user, or they were reported unfairly for “not that bad” behavior. These cries of malpractice have increased in recent years; today, in legion TikToks and Reddit posts, dating-app outcasts offer advice for circumventing the bans, such as setting up a new account using a Google Voice number or complaining to the BBB. But mostly they commiserate. “I get banned from the apps constantly. It’s making me really depressed because I don’t know how else to meet anyone,” one banned user wrote on Reddit. Another banned user replied that they had contemplated suicide. “Thanks Hinge, I hope your employees see this,” they added. “I’m not even really mad about it, just confused,” another redditor who had been banned from Match Group apps said. “Imagine getting ghosted by an app.”

These stories of revenge reporting raise questions similar to those that arose from the parable of “West Elm Caleb,” the 25-year-old furniture designer and prolific dater in New York who was accused en masse by women on TikTok last year of “love-bombing,” sending unsolicited dick pics, and ghosting. A condemnatory mob quickly raised the man up as a symbol of all that is wrong with New York’s dating scene. But in the coming days, onlookers began to suggest that maybe his behavior did not warrant being made a public enemy. Perhaps, if someone who has been rejected happens to have a platform on which to describe their anger and hurt — or if they have the option to report what happened to some higher power, including a tech company — anyone can be a rom-com villain.

One day in the summer of 2021, Erin Charaba, a 36-year-old woman in Washington State, tried to log in to Plenty of Fish and realized she no longer had an account. She then attempted to log in to Tinder, then Hinge, then OkCupid, all to no avail — it seemed she had been banned from every service owned by Match Group. She tried making accounts from other devices, but the apps saw through her IP disguise.

Banned users cannot know for sure whether they were revenge-reported because, in the interest of protecting victims of harassment, abuse, or assault, dating apps do not share the specific details of what led to each ban, and requests for information are fruitless. Users are left to replay their most recent app interactions just as one suffering food poisoning might replay their most recent meals to determine the culprit. (It was the taco whose beef had a grayish sheen. It was the man whom I accidentally ghosted.) A few hours before her failed log-in attempt, Charaba had rejected a man on Plenty of Fish — he had suggested that she come to his house, or he to hers, but she didn’t want to meet a stranger in private. She wondered whether he had reported her. Or maybe, she thought, she had been reported by a man she herself had reported a week earlier. “I wasn’t trying to hook up, and he sent me a really vulgar message,” she recalled. “I reported him on Tinder and then I saw him on POF [Plenty of Fish], and it’s possible he may have seen me too and reported me, because that happened within the same week.” She was spiraling in a kaleidoscope of possible explanations. Other users wonder whether their ban was done by man (an angry date, say) or machine (the apps’ artificial-intelligence systems, which, in addition to screening for fake profiles, can flag other behaviors such as solicitation). Becca Wolfley, a 29-year-old real-estate agent in Los Angeles, was banned from Hinge last July; she theorized that, by jokingly including her Venmo handle underneath a photo of her in a bikini, she had violated Hinge’s rules regarding solicitation (“One man did Venmo me $2,” she said). But she believes that someone she spurned had reported her, reasoning that her Venmo handle had been in her profile for almost a year without twanging any AI trip wires.

Some users immediately sense the machinations of a bitter former lover. I spoke to a woman I’ll call Abby who, last February, rejoined Hinge following a contentious split. She was finally ready for another relationship and badly wanted to meet someone, only to be banned days later. The email notification said simply that she had violated Hinge’s rules, but this didn’t make sense to her; “I had only had maybe, like, three pleasant conversations of ‘Hey, how is your day going?’ with a couple of guys.” She’d had a date set with a man she’d matched with on Hinge, but after she was banned, they never met up.

Being banned from a dating app wouldn’t even have registered as an inconvenience a decade ago, which was when, I realized recently with some horror, I took my first shy steps on OkCupid, a wobbly, wide-eyed fawn with no conception of the threats that lie in her path (a 33-year-old man who owned only one pillow). Dating apps were an expendable novelty whose chief value was entertainment, like Chatroulette. But these days, a ban can feel like being kicked out of the only bar in a small town. “The majority of my friends who are now either dating or engaged or married met on an app,” Abby said. “I feel as though I have this huge roadblock just because of my spiteful ex, who doesn’t want to be with me but doesn’t want me to move on,” she said.

Abby tried to ask her ex about the ban, but he would not respond to her texts and emails. She studied Hinge’s terms of service and, in an email to the company appealing the ban, addressed each of the terms and explained why it didn’t apply to her. “I was like, ‘I followed all your terms and conditions. I’m a good person,’” she said. Abby also explained the tension with her ex and shared his name. Even after several follow-ups, she never heard back. When Charaba was banned, she was busy studying and working full-time, so she relied on dating apps to meet people; though she was still able to access Bumble, which is not owned by Match Group, she didn’t like the app’s mandate to make the first move. “My dating life was very stale during that time,” she said. Meanwhile, videos recommending hacks to bereft singles have congealed into their own subgenre on TikTok and YouTube: “When it comes to resetting your profile, there’s different, let’s say, extremes you can go to,” said the host of the YouTube dating-advice channel Playing With Fire, before detailing a spectrum of solutions including deleting the metadata on your photos and creating an account on a friend’s phone — he used his mom’s.

Appealed bans can put app moderators in the tricky position of having to pick heroes and villains in the relationships of others. Because users can report offline behavior, such as racist remarks made on a date, as well as in-app behavior, moderators often have to evaluate situations they were not privy to. According to Alice Hunsberger, who oversaw customer support and content moderation at OkCupid for a decade and is now vice-president and global head of customer experience at Grindr, moderators must be “highly attuned to anything that seems sketchy or suspicious on both sides, including the user who initially made the report.” I sampled the difficulty of these evaluations when, recently, I was very moved by the impassioned dirge of a Reddit user bewildered by his ban from Tinder. He had done nothing wrong, he said. And maybe he hadn’t. But in the comments on the post, another user pointed out that the rest of his Reddit activity consisted of lewd remarks on photos of women. In love and war, trust no one.

At Grindr, at least, moderators, after assessing the reported behavior, may take factors such as power dynamics into account: If one user is perceived to have less social power than the other, they may get a second chance or a warning. This can empower moderators to protect trans users, for instance, from those who may weaponize bans. But there are no firm rules for calculating power dynamics. Hunsberger used age as an example to show how complex that calculus can become: If one user is 21 and the other is 45, the older user may have more social power — more money, more influence, more experience and savvy — while the younger user could be more vulnerable. But younger users may also be more desired on a dating app, and older users may feel less powerful. For accusations of dangerous offline behavior (such as sexual violence), apps employ even less flexibility: Bumble, for instance, will immediately block a user accused of sexual assault. And users accused of harassment can’t contact the reporting party, and their final ban from the platform is determined after further review, explained Rachel Haas, vice-president of member safety. (In late October, Bumble announced that it would remove users who were found to have falsely reported other users based on their identities.)

Banned users I spoke to understood and respected the high stakes of those scenarios but were still frustrated when trying to guess whether they’d been reported for being pictured indoors in swimwear, which is verboten on Bumble, for one (though the company is currently reviewing all its policies), or for some more egregious crime.

There are more complaints than ever about revenge reporting, but are there really more instances of revenge reporting? “Back in 2010, it didn’t occur to people that they could report other users for bad behavior. The internet just wasn’t there yet,” said Hunsberger. “Now, people really want a lot of intervention from social-media companies. And you hear a lot about how important it is for companies to keep people safe and protected and solve all of society’s problems — the problem of bullying — single-handedly, as a tech company.”

I’ve noticed that, in my cohort, reporting has quickly become the sledgehammer in the dating-app tool kit. In years past, we might have just unmatched offending users without a second thought, but now the “report” button beckons. Between the two poles of reporting for something truly petty (i.e., an ex, for having the gall to date) and reporting for dangerous, predatory behavior, there is a vast gray area in which users — few of whom, I’d wager, read the app’s terms of service — are left to determine which behaviors are and are not worth punishing.

I myself have reported one man on a dating app. Twice, he and I made plans to get drinks. The first time, he canceled hours before, which irked me; the second time, he stood me up, later claiming he’d gotten the time wrong. I wrote a detailed note to Bumble explaining what had happened and left his fate in the app’s hands, reasoning that if he was just a shambolic planner, he wasn’t a good dating-app citizen. One woman in Austin, the dating cesspool where I live, reported a man after a dinner-and-movie date. During the dinner, she had made a joke about not giving her date a ride, after which he jumped on the hood of her car, denting it. They still went to the movie, and he left the theater midway through the film and never returned. When the film was over, she texted him, and he claimed he’d run into a friend in the halls and they’d stepped out to smoke and had gotten locked out. Another friend told me she had once reported a man who, after she texted him following a fine but sparks-free first date to tell him she wasn’t interested, sent her a series of increasingly aggressive texts arguing for a second chance. These specific behaviors aren’t discussed in apps’ terms of service, but they inspired visceral reactions. On the flip side, the reported men likely believed they were behaving, if not romantically, at least acceptably.

A man in Austin whom I’ll call Matt — he said he’d prefer to use a pseudonym because “everyone’s gonna know, in Austin, Oh, that was that guy” — was bothered when Hinge sent an email notification to his matches announcing that “based on information regarding potentially fraudulent behavior,” he had been removed from Hinge. Matt said he had done nothing that could fall under the umbrella of “using a false identity or posing a significant risk of attempting to obtain money from other users through deceitful means.” He assumed someone he ghosted had reported him. (I have matched with Matt on various dating apps before. Our last interaction occurred on Hinge days before he was banned. Maybe I dodged a bullet; maybe he was The One.)

The ban didn’t disturb Matt’s sense of self or even his dating life (he was last spotted on Bumble). But he couldn’t believe that Hinge had informed his connections, using his full name, of a claim that he was sure was unsubstantiated. He had matched with co-workers and acquaintances, and while some of his suitresses DM’d him on Instagram to ask what happened, he was concerned about those he didn’t hear from — he has no idea who, of the women he matched with, received the message. Besides which, Austin really is a small town where it’s possible to swipe through all the singles in a 20-mile radius in one weekend. Everyone really might recognize him as that guy. (“There’s probably gonna be people for the rest of my life that look at me at the gym or something like, Whoa, he’s real,” Matt said.) He appealed his ban immediately, suggesting that perhaps updating his iPhone had caused the mishap, and the appeal was speedily denied. “I’m getting to the point where I’m gonna escalate to the CEO and COO and director of legal, and I’m gonna get a response,” he said in mid-September, in the wounded days after his ban. “I’m a wealthy person, so I will take this to the Supreme Court if I have to.” He ended up only emailing the CEO and ultimately chose acceptance.

Other banned users try sneakier tactics to reaccess the apps. Besides setting up new accounts using Google Voice numbers, many have tried installing apps on retired iPhones and subbing out their own SIM cards with prepaid ones. Grindr’s Alice Hunsberger told me that sometimes when users are especially dogged about escalating their bans — to Reddit, to the Better Business Bureau, to an app’s CEO — it emerges that they’ve been reported for behavior that mirrored that tenacity and aggression. “People’s experiences are so human and emotional on dating apps, so then any interaction you have with the company is an extension of that,” Hunsberger said.

We were ready for the intersection of technology and dating, but maybe we weren’t quite ready for the intersection of technology and all the tension that accompanies dating. Maybe pinning a ban on a spiteful report by another user — or even emailing an app’s CEO — is just an attempt to turn a tech-mediated interaction back into a human-to-human interaction. Maybe we all just want someone to text us back.