In the spring of 2022, Rose Gramuglia Santiago arrived at a penthouse suite in downtown Manhattan. There was a waiting room that was tastefully appointed with plants and books. In a darkened treatment room, Santiago lay in a reclining chair as a nurse explained the dose of ketamine she would receive through an intramuscular shot.

Santiago had the distinct impression that she went into a tunnel or outer space. In that first journey, she wondered if she had died. She did six sessions, twice a week for three weeks. “In one session, I recall screaming, ‘Help! Help! Am I dead? I can’t be dead! I have two kids,’ ” she says. “And there was no one there holding my hand or reassuring me that I was okay.”

Ketamine has been FDA-approved for use as an anesthetic since 1970 and is now being researched for the treatment of several mental-health disorders, including depression and substance abuse. In 2019, the FDA approved the ketamine derivative esketamine for treatment-resistant depression, including brand-name Spravato, which is administered as a nasal spray.

Ketamine’s latest reincarnation, however, is as an offering at upscale wellness centers. Because ketamine is FDA-approved, doctors can legally prescribe it off-label as an IV infusion, intramuscular shot, or lozenge to treat various psychiatric disorders—and with varying levels of therapeutic support—though it is often not covered by insurance. It has even been offered via telemedicine platforms that sprung up overnight in 2020—along with their targeted social-media ads—when telehealth regulations were loosened during the pandemic.

The existence of high-end clinics that offer ketamine-based services—and for many of these clinics, ketamine therapy is the exclusive service offered—may seem shocking or at least peculiar to those who knew the drug as “Special K,” a party drug popularized in rave culture that used to be associated by the mainstream with “K-holes,” not healing. “The reputation of ketamine over here is that it’s a dirty recreational drug, a horse tranquilizer,” says Celia Morgan, a professor of psychopharmacology at Exeter University in England, who is currently leading a clinical trial in the U.K. on ketamine-assisted therapy to treat alcoholism and has studied the benefits and side effects of recreational ketamine use. (In the U.S., federal law classifies ketamine as a Schedule III controlled substance, making it against the law to use or sell ketamine without a prescription or for recreational purposes.)

Santiago, 54, is a New Jersey–based psychotherapist in private practice who has herself had mental-health challenges that have required medications since her mid-20s. After seeing some of her patients’ depression symptoms improve on Spravato, Santiago decided to try ketamine herself at a clinic in New York.

A typical package at a clinic like the one Santiago visited can cost upwards of $4,000. It often includes a handful of sessions, supervision from clinical staff, and some form of “integration”—when a client talks about the experience and processes its meaning. (All of these clinics require a doctor’s prescription in addition to supervision by a trained medical professional.) The space was beautiful, Santiago says. But its luxurious amenities couldn’t support the intensity of her experience.

In the world of psychedelic-assisted therapy, you often hear about the importance of “set and setting.” Set is your mindset: what attitude you enter with. Setting is your physical environment, or the space around you.

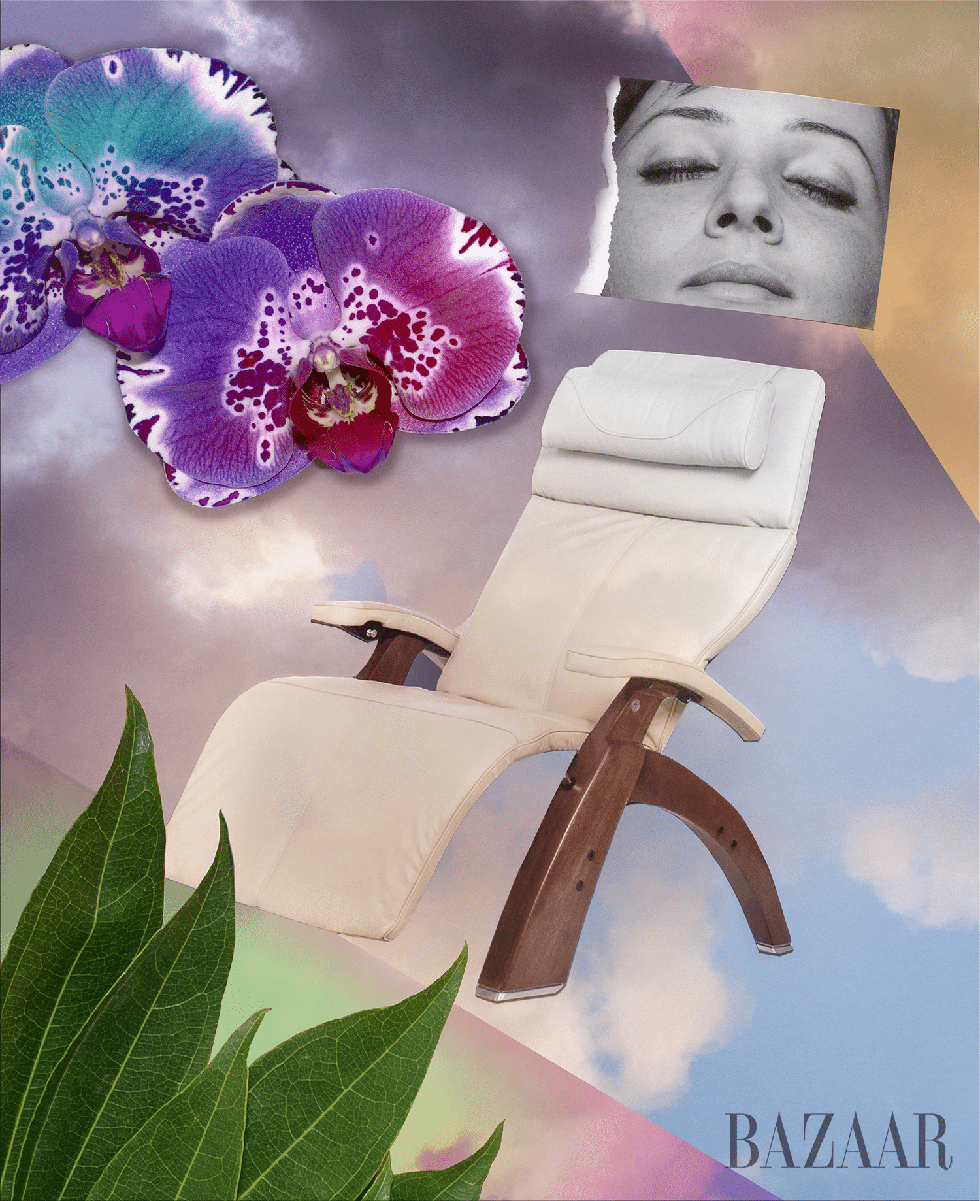

Ketamine centers have leaned into a highly specific setting. The clinics can have plant walls, bright and pastel colors, zero-gravity chairs, Moon Pods, beverage menus, and NFT art. They look familiar for a reason: They resemble what we know as “wellness,” which is not merely a word to describe how we’re doing but an industry, worth an estimated $450 billion in the U.S. alone, that comes with a specific visual and marketing language. It’s a nebulous category that includes nutritional supplements, yoga, crystals, Reiki, and green powders, all neatly packaged in a way that is designed to soothe and is pleasing to the eye. And now, it includes ketamine.

“I thought I would do the [intramuscular ketamine] and emerge as some kind of demigod,” Santiago says. “Spoiler alert: It didn’t happen. While the medicine had many benefits, overall, it didn’t provide the permanent relief from some of the mental-health challenges I periodically face. The cost of the treatment—nearly $5,000, most of which was not covered by insurance—was an investment I’m not certain I would have made had I known then what I have learned in the year since I underwent my first course of treatment. [These clinics] have spa-like qualities. It feels like a panacea.”

Santiago subsequently attended an experiential training that combined ketamine and Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy, which emphasized the “integration” part of the therapy, or the processing of it with a trained psychotherapist. She believes there is potential in ketamine but the therapeutic effect of “the medicine alone is limited.” And with the proliferation of upscale ketamine clinics, Santiago worries that “it’s going to be harder for insurance to cover the medicine and the process when it’s looking more and more like a retreat.”

Since ketamine is currently the only legally available form of psychedelic-assisted therapy in the U.S., it matters how these treatments look and how they’re marketed. This cultural rebranding of the drug has the potential to obscure some of the risks and limitations of ketamine-assisted therapy, which is still being studied for its safety and efficacy as a treatment for mental-health conditions.

Ketamine’s wellness window dressing is occurring at the same time as concerns are increasing about its off-label prescription, including its potential for addiction and adverse side effects. Ketamine’s positioning as a luxury wellness experience could also create barriers to access by encouraging the sidestepping of less costly treatment frameworks and demarcating it as something only for the wealthy, who can afford to take their well-being into their own hands.

One ketamine clinic in midtown Manhattan plays nature sounds, like water and crickets, and the space is filled with silk flowers in pink, purple, fuchsia, and turquoise. Art installations fill the space with NFTs and custom murals. Another New York clinic, part of a chain with locations throughout the U.S. and Canada, features a “signature moss wall” and provides weighted blankets, and the furniture is upholstered in soothing pastels. Many clinic websites proffer vague descriptions of the mind-body connection and the importance of states of mind.

Psychedelic-therapy settings should be comfortable and inviting. The recovery rooms at the clinic Santiago went to had colored pencils and markers you could draw with, “and you could have your tea, sit, or lie down or look out the window,” she says. “It was like you’re at a world-renowned spa and you had your massage and you go and sit and have your recovery time.”

After each ketamine session, Santiago was ravenous. She was offered tea and an array of snacks: chia-seed drinks, organic taro chips, healthy bars, and alkaline water. The amenities alone aren’t problematic; it’s that they are often offered in combination with nonspecific promises—science-washing that tends to make up wellness’s marketing language—paired with cost. “It’s the whole package that could potentially confuse some consumers,” says journalist Rina Raphael, the author of The Gospel of Wellness. “Vague terminology does really well in the wellness industry because you can kind of [fit] it to whatever it is that you need, whatever your biggest vulnerability is, your pain point, your biggest desire.”

This aesthetic resembles what’s been referred to as the millennial aesthetic or millennial minimalism. “It’s so clean! Everything’s fun, but not too much fun,” Molly Fischer wrote on The Cut in 2020, describing this look. “There’s a place to do laundry that looks like a spa, a place to get therapy that looks like the Wing”—the now-shuttered high-end coworking space for women that was known for its expensive white-oak and blush-toned mid-century-modern decor—“a boutique newsstand that sells scented candles and has an app.”

It’s called the “rhetoric of space” when a physical environment communicates what it’s about and who it’s for. The muraled walls are talking, and every weighted eye mask and Moon Pod chair is saying that these ketamine clinics have sought to position themselves alongside other wellness services.

This aligns with wellness trends outside of psychedelics. Analysts at the consulting firm McKinsey reported in 2022 that while products have dominated the U.S. wellness market so far, “services” are on the rise and might be the wellness focus of the future—with 45 percent of those surveyed intending to spend more on services and apps over the next year.

Wellness offers an alternative health intervention that is distrusting of other forms of medicine, that promises to be more “holistic” and get to “root causes.” Wellness can be seen as an outgrowth from the failures of the health-care system and society to care for people’s well-being. It’s often when people are not able to get the help they need that they turn to alternative practices. But it is ultimately individualistic and relies on people to act as consumers who buy their way to health.

In a recent talk at Horizons, a psychedelic conference in New York, Elias Dakwar, an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, called it the “ketamine industrial complex,” which offers not ketamine but Ketamine™ at “McKetamine clinics,” where “thoughtful discourse, evidence-based practices, and clinical rigor [are] replaced by buzzwords, new-age platitudes, and psychobabble.”

“From the user experience of the website, the advertising, the Instagram profile, and the experience of arriving at the clinic, being greeted, to the room design, the comfy bed, and the eye coverings, all of the built environment is part of this ritual performance of an idea of wellness,” says Colleen Derkatch, an associate professor of rhetoric at Toronto Metropolitan University and author of Why Wellness Sells.

Susie (using a pseudonym) is a former employee of a large ketamine clinic who says that while she thinks “set and setting” are key to good experiences, she saw a substantial portion of the budget at her company dedicated to design and marketing. “These types of ketamine companies, they [do] the wellness aspect of it because it’s Instagram-worthy or TikTok-worthy,” she says.

In some ways, it’s an odd choice that ketamine would vibe with wellness, where there’s usually a bias toward products and services that claim to be “natural,” even if that’s more of an ideological distinction. “Imagine something similar with opiates—if people started providing opiates in settings like this,” Morgan says. “People would be up in arms.”

Ketamine is a pharmaceutical product through and through. It’s listed as one of the World Health Organization’s essential medicines and used in hospitals as an anesthetic. “But when you attach that clean design, the millennial wellness aesthetic, to something like ketamine, it imbues it with a sense of goodness and benignness that could be misleading,” Derkatch says.

There are two opposing logics of wellness, Derkatch says. There’s the motivation of restoration, or the idea that by participating in wellness, you can restore your body to a prior state of functioning. Then, there’s the motivation of optimization or enhancement: making your body or mind as “good” as it can be. “Those two logics are trying to restore your body, restore your mental health, to a prior state of functioning but also trying to enhance and optimize it,” Derkatch says.

Wellness capitalizes on the idea of transcendence by creating a place through which a person can pass and transmogrify from one state to another new, self-actualized state. The aesthetics of the space reinforce that message. It doesn’t matter in the end that the product it’s selling isn’t “natural.” “If it’s built like a spa, customers might view it as a spa instead of what it actually is, which is a health intervention,” Raphael says. “Psychedelics are not on par with a facial. And by putting such a treatment in a more entertaining or soothing setting, you run the risk of distorting its purpose and effects.”

Ketamine is a potent substance that is still being studied for potential side effects and risks, including addiction, incontinence, kidney failure, and psychological impacts on the patients. While it’s a promising treatment modality, it’s also important to be mindful of the risks.

“A lot of people think with psychedelics that it’s like a silver bullet, or a panacea, and it’s not,” says Susie, who has training in mental health. “I think this aesthetic almost makes it seem like ‘Walk on in, get your vitamin infusion, and walk out a new person.’ That’s not how psychedelics or any sort of mind-altering substance works.”

“People are very keen on having these kinds of Holy Grail experiences,” Dakwar says, “and a feeling like one isn’t getting it right unless there is that total multisensory experience.”

The most salient overlap between wellness and the for-profit ketamine industry, and the underlying reason why both are popular, has to do with what they promise. Ketamine clinics are being positioned as solutions to a failure of care. “They tell a lot of customers what they want to hear,” Raphael says. “They tell them, ‘You haven’t been treated well by the medical establishment. They haven’t given you the answers.’ They’ll use tropes like ‘We get at the root issues of your problems or of your pain,’ as if medicine doesn’t do that as well.”

The way ketamine treatments are marketed sometimes gestures at the shortcomings of conventional mental-health treatments. Antidepressants don’t work, according to one clinic’s website. Another company’s site says that drugs like ketamine don’t just address the symptoms of “mental pain,” they “help us address their root causes.” In previous Instagram ads, that company quoted a testimonial that its service was like “five years of therapy in just a few sessions.” One clinic writes that it dreams of a world where people can reach their “full potential.”

Ketamine treatments provide a period of escape, something wellness also offers. “It provides a moment of respite, a moment of feeling good about doing something good for yourself,” Derkatch says.

There are ketamine providers that do offer a more nuanced pitch: “We understand that psychedelics are powerful medicines but not magic pills,” one says plainly on its site. “We don’t think ketamine is very effective on its own, and we worry about some of the more exuberant claims regarding the use of ketamine,” offers another.

In their 2015 book, The Wellness Syndrome, on the pressure to maximize our well-being, academics André Spicer and Carl Cederström wrote that the obligation to optimize the self could be a form of distraction away from social and economic justice. It could also pit the “unwell” against the “well”: If you’re not well, then you’re not doing enough to make yourself well.

Ketamine is a cheap drug—a dose costs pennies to make—and yet it’s been commodified into a product and experience that can cost patients thousands of dollars. There’s now an incentive for doctors to administer ketamine in a way that’s maximally lucrative. “It’s being sold under that whole wellness brand of [taking] personal responsibility for your health, which is really problematic because it doesn’t account for any social determinants of health,” Morgan says.

“Previously, it may have been something that people would have thought more deeply about, incorporating it in a manner that is equitable, because it’s so cheap,” Dakwar says. “With the market pressures being what they are, physicians themselves, who I think are ordinarily quite well-intentioned, may find themselves going down this well-trodden path.” It’s possible, for instance, to give ketamine to people on Medicaid. (Some clinics in Colorado now work in-network with the state’s Medicaid program to cover ketamine-assisted therapy.) But many times, “that’s not being done because that’s not the most lucrative way to do it,” Dakwar says.

In Sigmund Freud’s consulting room in Vienna, the couch wasn’t just a couch. It took center stage and was draped with a deep-red-and-blue Qashqa’i carpet and embroidered cushions. One of his patients, known as the Wolf Man, said it “must have been a surprise to any patient, for [it] in no way reminded one of a doctor’s office.”

The couch said something to those encountering it. “Everything here contributed to one’s feeling of leaving the haste of modern life behind, of being sheltered from one’s daily cares,” the Wolf Man said.

If psychoanalysis was once the treatment du jour, today, increasingly, psychedelic-assisted therapy is poised to take the spotlight. Since MDMA and psilocybin are still illegal under federal law, ketamine is starring in the first act. And the clinics dispensing it are sending a message through their spaces, just as Freud did with his couch.

Ketamine-assisted therapy could very well be an effective alternative or complement to existing mental-health treatments. But if that’s the case, then its branding as a form of wellness might run counter to that goal. It can delegitimize the research that’s ongoing, Morgan says, because a lot of people don’t take the wellness industry very seriously. “It’s a self-improvement culture, not serious medicine,” she explains. “It’s that quick-fix culture: You come for your infusion, you pay loads of money, and you’ll be better.”