A couple of summers ago, I went to the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin. I’d spent a lot of time in the city before, but I’d never visited the brewery. The tour is good. You can learn about how barrels are made, get your face printed in the head of a pint and, at the end, have a drink in a bar with a 360-degree view of the city. But what stayed with me most was something I saw there by accident.

One of the exhibit rooms was closed off, but only partially. Curiosity got the better of me, and behind the door, I found a room that was empty but for a table. On the table, there were a handful of editions of the Guinness Book of Records. I hadn’t thought about this book since I was in primary school. Back then, the Guinness Book of Records meant a big, brightly coloured, hardback volume containing 500-odd pages of pictures of people doing things like growing their hair very long or juggling knives. These were books that children gleefully unwrapped on Christmas Day and argued over with their siblings. As I flicked through the old editions – 1994, 2005, 2012 – I thought about the connection between Guinness the stout and Guinness the book for the first time, as well as a hundred questions I hadn’t thought to ask as an eight-year-old marvelling at the man with the stretchiest skin or the most needles inserted into his head.

Even now, in the age of YouTube and TikTok, when you can catapult yourself into fame, riches and recognition for feats of all kinds with nothing more complicated than your phone, the Guinness Book of Records continues, somewhat incredibly, to exist. The book, which since 1999 has gone by Guinness World Records, is still an overwhelming blizzard of wacky pictures and hard data.

But the company that publishes the book, also called Guinness World Records, is not the same as when I held my first annual, the green and silver 2002 edition. Sales of the book have declined in recent times, and the company has had to find new ways to make money – not all of which have met with the approval of the GWR old guard. When I spoke to Anna Nicholas, who worked as the head of PR for the book in the 80s and 90s, she lamented how things had changed: records are now more sensationalist, she said, to meet the demand of an audience that can see extraordinary things whenever they like on social media. “Guinness seemed to have had no issues with shamelessly and unapologetically selling out its devoted audience,” claimed one once-ardent fan in a 2020 blogpost.

It is strange to think of Guinness World Records – a business named after a beer company, which catalogues humanity’s most batshit endeavours – as the kind of entity that could sell out. At first glance, it seems like accusing Alton Towers or Pizza Express of selling out. But the deeper I delved into the world of record breaking, the more sense it made. In spite of its absurdity, or maybe because of it, record breaking is a reflection of our deepest interests and desires. Look deeply enough at a man attempting to break the record for most spoons on a human body, or the woman seeking to become the oldest salsa dancer in the world, and you can find yourself starting to believe that you’re peering into humanity’s soul.

On a windy late autumn morning, at the Olympic Park in east London, I found a young man pogoing with as much nervous solemnity as it is possible to pogo. Tyler Phillips, who had the aura of an Orange County surfer out of water, with a Hawaiian shirt and long hair tied back under a helmet, was there to try to break the record for most consecutive cars jumped over on a pogo stick. Behind him, five taxis were lined up side by side, with a gap of a few metres between each. A dozen Guinness World Records employees stood around to witness this attempt. Their number included a man in a navy and grey suit with a GWR logo on its breast pocket – a suit I later learned is reviled by many at the company for the high voltage of static it produces – who was introduced to me as Craig Glenday, the book’s editor-in-chief, who watched on with the unruffled air of someone for whom seeing a man pogostick over cars is all in a day’s work.

The atmosphere was tense. Final measurements were taken of the space between the cars (280cm) and their height (1.88m). Cameras were set up to document the feat. Phillips did some practice runs without the cars. On one occasion, he found himself sprawled on the pavement. I winced.

Finally, it was time. Everyone fell silent. Phillips steadied himself, and began. He nailed the first jump. Then the second, then the third. All breath was held. When Phillips jumped the final taxi and landed unscathed, he let the pogo stick fall to the ground and did a celebratory backflip, elated. “Yes!” he shouted, before running over to wrap Glenday in a bear hug. (Phillips has since beaten his own record, jumping over six cars in Milan in February 2022.)

Glenday has been part of GWR since 2001, and has, as a result, led an extremely varied professional life. He has suffered in the line of duty. One time on a trip to Istanbul to meet the woman who can protrude her eyeballs furthest out of her face, he received an insect bite that led to an infection that almost resulted in amputation. He was once stranded for a week in the southern tip of Chile with the band Fall Out Boy, who were trying to fly to Antarctica to break the record for the fastest time to do a gig on each continent. “Locals thought I was in Fall Out Boy. They were like, ‘Why is this fat old man in Fall Out Boy?’” he recalled.

A few weeks after witnessing Phillips’s feat, I visited Glenday at the Guinness World Records headquarters in central London. The company has more than 400 employees, and offices in New York, Dubai, Tokyo and Beijing, but the headquarters are in an unremarkable building near Tottenham Court Road. At first glance, the office looks much like any other. Until, that is, your eyes alight on items such as the puck from the longest ice hockey game (52hr 1min, 2002) and the broken toilet seat from a 2007 record-beating attempt at smashing the most toilet seats with your head in a minute (47). It is here that Glenday and his team put the book together, as well as make or break the dreams of record-setting hopefuls all over the world.

Glenday was keen for me to try breaking a record myself. He browsed through their database of 60,000-odd records to find one that was easy to do in the office and not impossibly difficult to beat. We settled for the longest time standing on one leg blindfolded. The record stood at 31min 14sec. Glenday printed off six pages of guidelines. For more complicated records, the guidelines can run to dozens of pages, but these were relatively simple. I read that I was not permitted to rest my other leg on my standing leg, that I must have two independent witnesses timing my attempt with stopwatches accurate to 0.01 seconds, film my attempt for Guinness’s verification, and be blindfolded even in the event that I am in fact blind.

Like all record attempters, I was allowed three goes. My first attempt clocked in at a pathetic 3.4 seconds. Then 25.06. Then 31.03. I’m somewhat ashamed to say that a tiny part of me was surprised. As I read through the guidelines, a voice inside me had whispered: “What if this is my secret skill? A hitherto undiscovered genius I have: standing on one leg blindfolded?” I didn’t really expect to break the record. But the tiny possibility was thrilling.

As a child, I thought of Guinness as something like a mystical higher power, or some kind of government body. It seemed like it must have always existed. Not so. It began with an argument in 1951. The managing director of Guinness, Sir Hugh Beaver, was on a hunting trip in Wexford, and his party couldn’t agree which game bird was fastest. This dispute seems to have stuck with Beaver. Thinking back on the incident three years later, it occurred to him that these kinds of arguments must happen all the time and there would surely be an appetite for argument-settling answers in the form of a compendious book that catalogued world records, as well as the extremes of the natural world. This volume could be distributed to pubs that sold Guinness. It could also be sold in shops, and provide another revenue stream for the brewery.

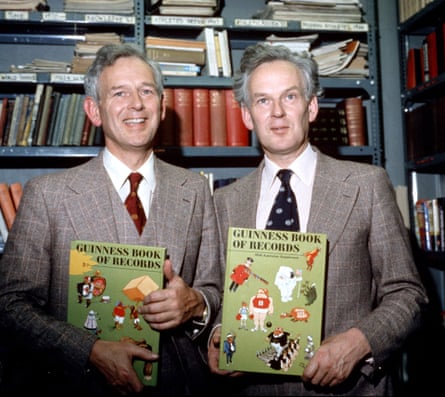

For help, Beaver turned to identical twins named Ross and Norris McWhirter who ran a fact and figure-provision service for the newspapers of Fleet Street. The first edition, published in 1955, was shaped by the brothers’ eclectic personal taste and sense of propriety. Norris hated popular music because he thought it was “ephemeral”, and so limited the number of records in this field. No records to do with sex were included, because the twins thought, as Norris put it in 1954, “You can get those records out of medical literature, but ours is the kind of book maiden aunts give to their nieces.” Instead, readers could discover the highest lifetime milk yield of a cow (325,130lb, held by a British friesian called Manningford Faith Jan Graceful). The foreword to the first edition read: “Guinness, in producing this book, hopes that it may assist in resolving many such disputes, and may, we hope, turn heat into light.”

The book became wildly popular, and the annual Guinness Book of Records was born, with the McWhirter twins remaining at the helm for the next two decades. In 1975, however, Ross was shot dead by the IRA for publicly offering a £50,000 reward for information leading to the conviction of terrorist bombers in Britain. Norris continued alone, only stepping down as editor in 1985, and remaining in an advisory role until 1996, when he stopped working for GWR. “The book was Norris and Norris was the book,” was how Anna Nicholas put it to me. Under his editorship, GWR headquarters became a homing beacon for the UK’s biggest oddballs, who showed up claiming everything from the heaviest sausage dog to the world’s largest toothbrush. (Norris was also fervently rightwing – an enemy of trade unions, the European Union and sanctions against apartheid South Africa – though these beliefs were not evident in the book he edited.)

Today, anyone arguing with their friends about the fastest game bird (the red-breasted merganser, at 130 km/h) would, of course, consult the internet, not the latest edition of Guinness World Records. There is a decidedly analogue feel to the company – the objects on display at the office, the physicality of the book itself. But when I sat down to chat with Glenday in the GWR headquarters, in a meeting room named after Elaine Davidson, the world’s most-pierced woman, he made the bold claim that the age of information on demand has not killed the need for the book. In fact, he continued still more boldly, it may have actually helped them.

He positioned GWR as a kind of factchecker of the absurd. GWR liaises closely with experts in fields as diverse as surfing, architecture, extreme weather, robotics and jigsaw puzzles. Glenday argues that the book serves as an authority in a way that the great wash of information on the internet can’t: they know what the records are because they’ve measured them, taken video evidence and can point to the guidelines they checked the record against. “You might as well just shout a question into the street and see what answer you get back: that’s what the internet is like,” Glenday said, sounding a little like someone who had time-travelled from 1995 to speak to me about a thing called the internet.

There are, I posit, four types of Guinness world records. Type one: records broken without being record-breaking attempts. The most words in a hit single (Rap God by Eminem at 1,560); the most venomous viper (the saw-scaled viper Echis carinatus). Type two: sporting achievements. The fastest boxing knockout (4 seconds), the longest tennis match (11hr 5min) and so on. Type three are the ones that stick in our memories from childhood: records that seem to exist purely in order to be records. The largest toast mosaic (189.59 sq metres), fastest time to roll an orange one mile with your nose (22min 41sec), and perhaps the most iconic of all, longest fingernails (42ft 10.4in). And then there is the fourth kind: marketing stunts. In 2020, for instance, Bush’s Beans set the record for largest layered dip (493kg and 70 layers) to “celebrate the Super Bowl”. Two years earlier, Moontower Pizza Bar in Burleson, Texas created the world’s largest commercially available pizza at 1.98 sq metres, retailing at $299.95, plus tax.

For some observers, the existence of this last category is a sad reflection of how far the company has fallen. “They’ve lost the intellectual integrity that the twins had,” Norris’s son, Alasdair McWhirter, told me. “For them, it was a knowledge-based quest, and they had tremendous enthusiasm for that. Whereas now everything is done to make money.” Since 1997, when Guinness merged with Grand Metropolitan, another conglomerate, and formed Diageo, GWR has had to operate as a self-supporting business rather than the novelty arm of a beer company. (GWR is now owned by the Canadian conglomerate the Jim Pattison Group.)

These days, GWR Consultancy, which was introduced in 2009 and offers adjudication services to customers for a fee, accounts for half of the company’s revenue. Brands looking to break a record as part of a publicity campaign cannot exactly buy their way into the book, but a fee starting at £11,000 gets them the services of a GWR consultant, who can help them brainstorm which record the company could attempt for most viral PR, and an official adjudicator for their attempt. In 2022, Mastercard got a bunch of footballers to break the record for the highest-altitude game of football on a parabolic flight: 20,230 ft, played in zero-gravity conditions on a specially outfitted aircraft. Perhaps slightly less impressively, in 2021, Currys created the world’s largest washing machine pyramid (44ft 7in) in a car park in Lancashire. And like any business, GWR itself needs to magic up some publicity every so often. Announcements pegged to buzzy news events, like Elon Musk now holding the record for “largest amount of money lost by one person”, are astonishingly potent acts of self-promotion, guaranteeing that the words “Guinness World Records” will appear across the world’s most famous media brands from Sky News to CBS to the Hindustan Times to the Guardian.

I asked Glenday what he thought of complaints that the organisation had changed for the worse: more money, less soul. “We’ve appended that corporate side to the business, rather than replaced anything,” he said. “It’s that old, ‘nostalgia ain’t what it used to be’ thing.” Besides, he added, most of these records-as-marketing-stunts don’t make it into the book.

GWR has faced other criticisms since the introduction of the consultancy services. The most serious of these concern Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, who ruled Turkmenistan between 2007 and 2022. (He has since been replaced as president by his son, Serdar.) Berdymukhamedov was a dictator whose regime carried out arbitrary detentions, controlled the media, persecuted homosexuals and women seeking abortions, and discriminated against ethnic and religious minorities. He was also a keen GWR fan. Between 2011 and 2018, his government and bodies linked to the government made a total of seven applications to GWR for record attempts. According to his wishes, the city of Ashgabat sought and broke the record for “the highest density of buildings with white marble cladding”. A tower he ordered to be built won the record for the largest architectural image of a star. (GWR told me that it could not reveal how much money Turkmenistan had paid for GWR Consultancy services.)

When I brought up GWR’s work with Berdymukhamedov, Glenday admitted that this had been a misstep, because of Turkmenistan’s human rights record. The company is now more careful about their association with anything where they think there’s “some political angle”, he said. “If you’re a school, and you come to us from Turkmenistan and want to do a record attempt, that’s totally fine. But if it’s organised by the minister of culture, then you start to think well, wait a minute. Why?”

At the core of GWR lies the work of its 90 or so adjudicators. It is their duty to separate fact from fiction and, insofar as the institution can be said to have dignity, they must preserve it. Each one must wear a special jacket – the same jacket that Glenday was wearing at the pogo stick attempt – at every event, no matter the weather. They are not permitted to eat or drink alcohol while on the job, and they can’t fraternise after hours with the record-setters. The adjudicators bring the certificate, framed, to each record-breaking attempt, and if you fail they take them away to be shredded, because sometimes people have gone through the Guinness bins to steal them.

It used to be that GWR adjudicators needed to be present for any record attempt – in the early days, this usually meant Norris McWhirter himself. Mick Meaney, an Irishman who attempted to beat the world record for longest live burial in 1968, lived in a coffin under a builder’s yard in Kilburn for 61 days. He survived on “steak and cigarettes” delivered to him through a tube, and defecated in a specially fitted extraction pipe. But he forgot to invite a GWR adjudicator to verify his attempt in person, and so was denied his place in the book. “One adjudicator flew to Sydney to weigh a risotto, and then got back on the plane again. That’s a lot of time out of the office,” Glenday said.

Not everything can be a record. The adjudicators receive as many as 100 requests for new record creations a day from all over the world. In judging their suitability, GWR applies five criteria. Records must be standardisable, measurable, breakable, verifiable and, crucially, contain only a single superlative. The fastest marathon: fair game. The tallest man: fair game. The fastest marathon run by the tallest man: nope. There also has to be a sense that anybody else might want to break said new record. “One example application we got was the longest drawing of an evil train,” Glenday said.

Today, most adjudications take place remotely, with video evidence being scrutinised. If you want to have an adjudicator present at your record-breaking attempt, either in person or by video link, you would have to pay £6,000 for the privilege. This would also get your record attempt fast-tracked for approval. Otherwise, you would have to submit video evidence of your attempt to GWR through its online portal, and wait a few months to hear whether it was satisfied that you had broken the record. (Not many individuals pay £6,000. The big money, for GWR, comes from the work with brands.)

Glenday, like many Guinness employees, from the CEO down to junior office workers, has undertaken the official adjudicator’s training. This takes about a week, and involves media training, public speaking guidance, codes of behaviour and a crash course in how to use various types of measuring equipment, such as a sound meter to record, say, the loudest burp by a male (112.4 db, roughly as loud as it is possible to blow a trombone). Adjudicators are often sent across the world on very little notice, and aren’t told what the record attempt is until they have accepted the mission. Every record has to be treated with the same gravity. “It sounds ridiculous, things like someone skipping in swim fins,” one longtime adjudicator, Alan Pixley, told me. “But they’re practising every day, they really believe in it. I have to treat every adjudication as if it’s Usain Bolt running the 100 metres.” Adjudicators speak gravely of the disappointment of having to deny certificates to people who fail their attempts. It especially breaks their hearts to refuse records to schools and charities – but sometimes, it must be done.

Adjudicating can be a dangerous business. Glenday recalled one particularly sticky situation in Moscow, where he had come to assess an attempt to do the largest pouring of concrete in history. It was very cold – “there was horizontal snow” – and the engineers on site declared that it was technically impossible to pour the concrete. “So they were trying to get me to just fake the presentation as if it had happened, and they could film it and slice it into another presentation,” Glenday told me. “And I said I can’t really do this. But I’m standing on the edge of a massive hole in the Moscow financial district before it was the financial district, which is just a bit of a wasteland. And it looked like something from a horror movie. And I thought I was going to disappear into the hole and that would be it.”

Glenday wisely decided to cooperate. “It’s very hard to say no. So the rule is just do it. And then just get out, and revoke it the next day. It’s quite pressurised, a lot of it.”

Beyond the regular people, who have a particular record they want to break, and the businesses, who want to break a record for publicity, there is another category of record breaker: people who have turned record breaking into a discipline in its own right, with its own rules and skillsets. These are the super record-breakers, the gods on the Mount Olympus of GWR. “They have a certain aura around them, an attitude, a presence,” Pixley told me, “and it’s important not to be intimidated by that.”

Super record-breakers are the kind of people who try to break a record a week. David Rush, a teacher living in Boise, Idaho, broke his first record – the longest duration juggling while blindfolded – in 2015, and since then has broken more than 250 more. No human in history has caught as many marshmallows fired from a homemade catapult in the space of one minute (77), nor has anyone put on more T-shirts in 30 seconds (17). “Not only can you get better at anything,” Rush told me in a Zoom interview, “but the belief you can get better at something dramatically improves your ability to do so.”

One of Rush’s frequent direct competitors is Silvio Sabba, a gym owner from just outside Milan and the man who currently holds the most Guinness World Records: 193. Sabba’s particular genius is in identifying what are known as “soft records”: ones that most people would be capable of breaking, if they approached it in the right way. For Sabba, record-breaking is not primarily a physical feat but a strategic one. In his 13 years of record breaking, he has learned never to smash a record, but to break it just a little, so that if anyone subsequently bests it, he can go back and surpass their attempt without too much additional training. “I do like to defend the records I hold,” he told me.

Almost all the super record-breakers spoke of the camaraderie they shared with their peers; they were a community. Many used the word “family”. And if record breakers are a family, there is a clear patriarch: Ashrita Furman, record breaker for more than four decades, and inspiration to many of the younger generation. Rush has a childhood memory of seeing Furman break a world record on television by balancing 50 pint glasses on his chin. Andre Ortolf, a 29-year-old German who specialises in eating things very quickly (the more liquid the food the better, apparently), said that his first GWR book was the 2004 annual. On page after page, he saw Furman’s name. “I realised, OK, this guy’s breaking nearly everything. So I can break one.”

Furman, who is now 68, lives in Jamaica, New York. When I arrived at his house last summer, I found him on his front porch, neatly dressed in a yellow polo shirt and New Balance trainers. He invited me to go round the back of the house to the garden, and then went inside to fetch something, jumping the four steps of his porch in one smooth leap.

Furman keeps his GWR certificates, more than 700 of them, in a clear plastic box in his wardrobe. He has so many that he has stopped even applying for the certificates when he breaks a record. This is a man who knows precisely how many forward rolls will make you throw up, which brand of eggs are easiest to balance on a flat surface and which muscles in your feet fatigue first if you stand on a yoga ball for too long. He pulled out his copy of the first Guinness book, evidently well-thumbed, and read me the quote in the foreword about turning heat into light with the reverence an evangelical might quote a passage from the Bible.

Furman’s journey started when he was 16 and disillusioned with life. One day he met an Indian spiritual teacher living in Queens called Sri Chinmoy. He decided then and there to follow him for the rest of his life. Ashrita is not his given name – that is Keith – but a name he chose for himself, a practice adopted by all followers of Sri Chinmoy. A few years later, some of his followers were training for a 24-hour bicycle race around Central Park, as a way to achieve self-transcendence through physical exercise. Furman, having been unathletic all his life, hadn’t wanted to compete. But he began to feel guilty for shirking and signed up a week before the race. The night before, the competitors gathered to meditate with their teacher. “And he said, just for fun, how many miles do you think you’re going to do in the race? The best riders thought they could do maybe 300, 325 miles. And my teacher says, so Ashrita, how many miles? 400 miles?”

Furman went straight home, fearing that he would die in his attempt, and wrote his will, leaving his worldly possessions, including a rabbit and some birds he used to do magic shows for kids, to his roommate. The following day, with no training, he cycled 405 miles, and tied for third place. He did it – “simply”, he says – by meditating. “As soon as I stumbled off the bike, I connected to the Guinness book, because I’ve always been a big fan. I thought, if I could do this, then I can break a Guinness record. And I want to do it not to get my picture in the book, but to tell people about the power of meditation.”

He has used this power to break hundreds of records. He has pogoed in Antarctica, walked 80.95 miles with a milk bottle on his head, won a potato sack race against a yak in Mongolia, all to promote Sri Chinmoy to a wider audience. “I realised that I have this capacity. And it’s not just me,” he said. He echoed what Rush had told me: being the best at something is not innate. It’s something that you decide to do.

I mentioned my pitiable attempt at the standing on one leg record. Furman’s eyes lit up. “You could do that one, you could … 32 minutes is not a long time. See, that’s a soft record,” he said, a grin breaking across his face, “that makes me think, wow, I could do that.”

Furman is one of the old guard who believes that the business of record breaking has become too much of a business. “Things have changed a lot with Guinness,” he told me. “It was much more personal, back in the day. For years, when the book came out, I would go out to lunch with the editor, or the head of PR. I think we kind of lost that. I know Craig [Glenday], I think he’s a great guy, but really it’s become more of a big business. And I understand that. It’s the way the world has changed.”

These days Furman is more interested in helping others achieve their record-breaking goals than in breaking records himself. To Furman, records are a measure of human progress. As such, he is happy when they are broken, and especially happy when they are broken with his help. “It’s a really positive thing. I mean, we need more positive things in the world, right?”

Encouraged by Furman’s belief in my abilities, I spent the weeks after my visit practising standing on one leg blindfolded. Initially, I was very bad. Then, soon enough, I wasn’t. I got up to 12 minutes and eight seconds before it occurred to me to check that the record had not been broken since I tried it at the Guinness office. It had. It now stood at 1hr 6min 57sec, broken in early 2022 by a man named Ram Phai in Uttar Pradesh, to honour his father, who is a big fan of Guinness World Records. (GWR is massively popular in India, another consequence of GWR reaching a broader audience thanks to the internet, Glenday told me.) After reading this, I was demoralised, and I gave up. The reason I didn’t break the record was not because I was incapable of doing it. It was because I didn’t want it enough.

Or perhaps I didn’t want it for the right reasons. GWR may be a business, but for the people pursuing the records, it is far more than that. George Kaminski, who held the record for the largest collection of four-leaf clovers until 2007, collected every one of them from the grounds of prisons in Pennsylvania where he was serving a life sentence. The woman with the longest fingernails, Diana Armstrong, does not have the longest fingernails because she wants her picture in a book. She has the longest fingernails because she decided never to cut them again after her daughter, with whom she used to get her nails done, died aged 16.

I asked everyone I spoke to whether they thought that keeping track of world records was important. “What is the definition of important? It’s what you or other people find important,” Rush said. The events we celebrate in the Olympics were initially chosen to demonstrate some kind of martial prowess: throwing spears, running quickly, wrestling an opponent. We’ve added new categories: basketball, skateboarding. But most of the achievements we value, in the Olympics as elsewhere, are arbitrary. Guinness World Records are a way of acknowledging the value of human endeavour of any kind: of celebrating achievement in the abstract. Recalling what had made working at GWR magical to her, Nicholas said “it was the one part of society that was totally, utterly, inclusive. It didn’t matter who you were or where you were in the world, you could be a phenomenal record breaker in your own area, and leave your mark on the world.”

I spoke to Glenday again late last year, a few months after my meeting with Furman. He’d had a frustrating week: an attempt at the highest bungee jump that ends with toast soldiers being dipped into boiled eggs had been scuppered by unusually high wind. But he was not defeated. “Reading about things that you’ve never even conceived of, or can’t ever have imagined, is just thrilling,” Glenday told me. “You get an adrenaline hit from that discovery, and we still get it now. I still get it when I see things that I’ve never seen. Like this year, we’ve got a dog and a cat on a scooter together.”

Not long ago, I logged on to Zoom to watch Ortolf, the young record breaker with a gift for eating very fast, attempt to break his next record: the shortest time to sort 500g of peanut M&Ms by colour, using only one hand. The holder of the title, a man in Perth, had achieved this in 1min 33.03sec. Ortolf, at his house in Augsburg, a small city just outside Munich, had seven bowls of equal height laid out in front of him and a camera set up on a tripod. He opened the bag of M&Ms, emptied them into one of the bowls and showed the now-empty bag to the camera, to me, and to his other witness, a friend.

He sat down and placed his left hand behind his back, and his right hand flat on the table. He took a few steadying breaths. The timer started, and he began. He had developed a technique: blue first, as he finds them easiest to spot.

The only sound was Ortolf’s measured breathing, and the rhythmic ding of blue chocolate hitting ceramic. Then brown, green, yellow, orange. The final colour he could do in scoops. As the last handful hit the bowl, his witness stopped the clock. One minute, 27.45 seconds. Another record in the bag, his 104th.

Ortolf laughed, a wide smile splitting his face. “Yes,” he said, “yes.”

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, listen to our podcasts here and sign up to the long read weekly email here.