Updated on November 19 at 6:20 p.m. ET

Make no mistake: Ticketmaster deserves the scorn that it is currently receiving from Taylor Swift’s listenership, a population of such size and power that it probably merits a spot in the United Nations. Earlier this week, the company’s just-for-fans presale of tickets to Swift’s 2023 concert tour was riddled with bugs and delays. More shocking, Ticketmaster then canceled the general-public sale because of technical issues and—are you ready for it?—a lack of inventory. Yes, amid much confusion, the presale became (for now) the only sale. The fiasco appears to present a tidy parable about what happens to institutional competence when a company holds what many lawmakers allege to be monopolistic power for more than a decade.

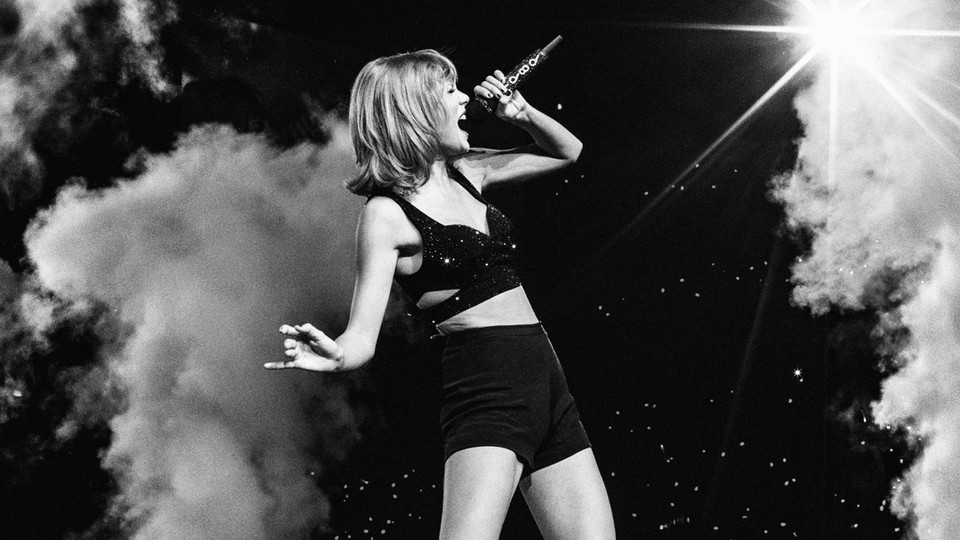

Yet the story is bigger than Ticketmaster, and perhaps bigger than even Taylor Swift. (She weighed in today: “It’s truly amazing that 2.4 million people got tickets, but it really pisses me off that a lot of them feel like they went through several bear attacks to get them.”) The 32-year-old singer-songwriter is dominating at a time when live tours are, by many estimations, costlier to embark on, more difficult to pull off, and more in demand than they ever have been. Three big trends may explain why a series of annoying glitches has taken on the air of an international incident.

The Swift of It All

According to Ticketmaster, the desire for Swift’s tickets smote all records and reasonable expectations. Fourteen million users—and bots—tried to buy tickets, the company’s chair said, and a Ticketmaster blog post reported that the presale traffic eclipsed any previous peak by a factor of four. To meet such demand, Swift would have to play “over 900 stadium shows (almost 20x the number of shows she is doing),” Ticketmaster said. The company’s numbers raise a lot of questions—how much of a role did resellers play, for example?—but the underlying takeaway seems correct: The breadth and intensity of Swift’s fandom right now is extraordinary.

Think about it. A decade and a half into superstardom, Swift somehow retains the fascination of the most important constituency for pop music: teenagers. But she is also a cross-generational object of acclaim working in her prime, consistently winning Album of the Year Grammys and smashing sales records (her latest album, Midnights, had better first-week sales than any other album by any other artist in the past seven years). On top of that, she has made herself a de facto legacy act by rerecording and promoting her albums that came out years ago. On top of that, the coronavirus pandemic built up demand by keeping her off the road—and also pushed Swift to create the fandom-expanding curveballs of Folklore and Evermore. She has released four new studio albums since her last stage show in 2018, and her forthcoming tour’s title, “The Eras Tour,” hints that she will make a point of playing not just the recent hits.

What are the precedents for her present sway? Names such as Michael Jackson and Madonna come to mind, but when I emailed Steve Waksman, the author of the history book Live Music in America, he mentioned Jenny Lind, the Scandinavian opera singer whose 19th-century rise to fame “was a prototype for what modern pop stars became.” Some fans of Lind’s paid the modern equivalent of thousands of dollars at auction for tickets to see her perform. In our current maelstrom of circumstances, I wonder if Swift’s draw is at all like what the Beatles’ would have been if the band—which stopped touring more than three years before breaking up—had reunited in the ’70s (and if they were, just as fantastically, known for better concerts).

Of course, comparisons of this nature are hard to make. “In terms of tracking demand for concert tickets, there would have been no way to quantify that sort of thing until fairly recently,” Waksman cautioned. “Pre-Ticketmaster … it would have been all but impossible to know just how many people were trying to get tickets for a given show or tour. The kind of popularity Swift has, and the way that popularity translates into demand for tickets to her shows, is pretty squarely a product of the move of concert ticketing onto the internet.” Which brings us to the second factor in this mess: the online world.

In a Digital Era, Live Music Is More Important Than Ever

Swift’s success has long been linked to the technologies that fans use to connect with her. She used social media to turn the old-school concept of a fan club into something like a metaverse. She has sparred with digital distributors—Apple, Spotify—when their business interests haven’t lined up with her own. And, with her extravagantly staged tours and her famed in-person listening parties for fans, she has long capitalized on a modern reality: When streaming makes music more plentiful and disembodied, the rarity and tangibility of live experiences take on new value.

That value was clear before the pandemic, when revenues for the live-music industry were trending to unprecedented heights—a rise also facilitated by digital ticketing. Artists had even begun toying with new models to capitalize on their fan base. In 2020, Swift planned a unique sort of tour involving her hosting two U.S. “festivals,” one on the East Coast and one on the West Coast. The pandemic-thwarted itinerary would have fit with a trend of stars posting up for residencies in select cities. When demand is high enough, an artist can count on their fans coming to them.

The Pandemic Has Messed Up the Live-Music Ecosystem

The pandemic has pushed that demand even higher. But the costs and stresses of touring have also, by all accounts, skyrocketed lately. In the past few months, big-name talents—including celebrities such as Justin Bieber and Shawn Mendes, as well as indie types such as Animal Collective and Santigold—have canceled or rescheduled tours. The cited reasons, as varied as money and mental health, point to an undeniable reality: Something is off about the live-music ecosystem. In a recent letter to fans, the pop star Lorde explained the situation:

Let’s start with three years’ worth of shows happening in one. Add global economic downturn, and then add the totally understandable wariness for concertgoers around health risks. On the logistical side there’s things like immense crew shortages (here’s an article from last week about this in New Zealand), extremely overbooked trucks and tour buses and venues, inflated flight and accommodation costs, ongoing general COVID costs, and truly. mindboggling. freight costs … Ticket prices would have to increase to start accommodating even a little of this, but absolutely no one wants to charge their harried and extremely-compassionate-and-flexible audience any more fucking money.

Such problems, Lorde noted, are far more perilous for smaller artists. And we still don’t know exactly what structural factors led to Ticketmaster’s flailing this week. But Swift nevertheless appears to be affected by a widespread trend: Across live music, supply and demand aren’t matching up, and core systems are breaking down. A winner-take-all dynamic may be emerging in which only the biggest stars can afford to gig—but are then overrun with demand, leaving listeners feeling frustrated and fleeced. The fans who did snag tickets to see Swift should cherish them. Meanwhile, Ticketmaster had better be giving its software a close look: Rumors are that Beyoncé and Rihanna will soon embark on their first tours in years.